The Tzaddik of Leningrad Looks Back 30 Years After the Fall of the USSR

by Dovid Margolin – chabad.org

In the winter of 1986, Yitzchak and Sofya Kogan finally received the Soviet exit visas they had waited 14 years for. Naturally, they were thrilled—but much had changed since they first applied in 1972. Like thousands of other Soviet Jews, they still wanted to leave the USSR and settle in a place where they could freely observe Judaism and raise their children as proud, practicing Jews. But in the intervening years, they had become ever-more-active leaders in Leningrad’s Jewish underground. Yitzchak’s renown was such that he even came to be known as the “Tzaddik of Leningrad.”

“I knew that the Rebbe [Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory] wanted that anyone with a leadership role or who influenced others should remain where they are, so I wrote to him asking what we should do,” Rabbi Kogan, 75, told me recently. “The answer we got was unequivocal: The permission we received was miraculous, and we should leave. That’s what we did.”

The farewell scene at the airport was an emotional one, as the Kogans’ fellow refuseniks, many of whom had become their students, gathered to see them off. As far as anyone knew back then, such goodbyes were forever, and so the young Jews sang and danced as the airport’s contingent of KGB officers looked on.

The Kogans flew to Vienna, where they were greeted by Chabad-Lubavitch emissaries dispatched by the Rebbe, and then on to Israel, where they intended to make their home. Three weeks later, on Thursday morning, Dec. 11, 1986 (9 Kislev, 5747), Yitzchak and Sofya arrived in New York, driving straight to Chabad-Lubavitch headquarters at 770 Eastern Parkway in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. Knowing of the Rebbe’s special love and affinity for Russian Jewry and having heard of the Kogans’ courageous activism behind the Iron Curtain, a large crowd gathered to witness the refuseniks’ first encounter with the Rebbe. As the Rebbe walked into the synagogue for morning prayers, Kogan stepped forward and loudly recited the shehecheyanu blessing in honor of the occasion, with the Rebbe responding amen.

“Then I said, ‘I am Izya Kogan, I just came out of the Soviet Union,’ ” Kogan recalls. “The Rebbe looked straight at me, and that first look made the greatest impression on me. It transformed me.”

That day the Rebbe went to the Ohel—the resting place of his father-in-law, the Sixth Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, of righteous memory. After the Rebbe returned to 770 for evening prayers, one of his secretaries told Kogan the Rebbe wanted to see him and his wife in private. That evening, the Kogans entered the hallway outside the Rebbe’s office, emerging more than two hours later. Five days later, as the Kogans prepared to head back to Israel, they had a second, 35-minute-long private audience. Both of these meetings were well out of the ordinary as private audiences had completely stopped years earlier.

The Kogans returned to Israel, where they began working with Russian Jewish immigrants arriving in ever greater numbers. Kogan also worked on Chabad’s Children of Chernobyl emergency airlift and served in the Israel Defense Forces. Then, in 1991—just five years after Kogan had received his long-awaited exit visa—the Rebbe sent Kogan back to the Soviet Union as part of the team tasked with bringing the library of the Lubavitcher Rebbes to its rightful home at the Library of Agudas Chassidei Chabad in Brooklyn. Kogan went to Moscow assuming this would be a temporary assignment, but a year passed and the mission was yet to be completed. His family was in Israel, he was in Moscow—where was his permanent place? Once again, Kogan turned to the Rebbe, asking what he should do. “As long as you feel the strength to continue there,” the Rebbe responded, “then I give you all my blessings.”

Kogan had his answer. He was immediately joined in what was then still the USSR by his wife (who passed away in 2009) and family, and has never left. “I’ve been here 30 years now,” Kogan says. Around the same time, in 1992, Kogan became the rabbi of the Bolshaya Bronnaya Synagogue of Agudas Chassidei Chabad in central Moscow. In the years since, he’s restored the synagogue and transformed it into a gleaming, active, five-story Jewish community center.

With the world marking 30 years since the miraculous fall of the Soviet Union, I spoke with R’ Yitzchak about his Jewish education in the USSR; the profound, sustained impact of the Chabad Rebbes on Soviet Jewish life, including his own; and what transpired during those long audiences with the Rebbe.

A Soviet Jewish Education

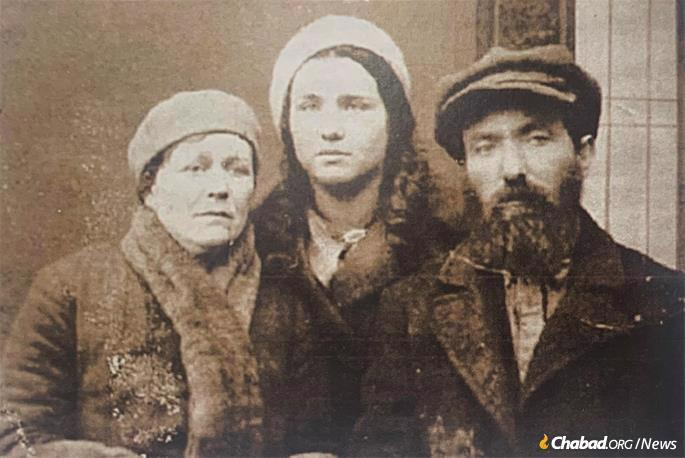

Yitzchak Kogan was born in post-war Leningrad in 1946, the elder of Avraham and Riva Kogan’s two sons. His father was orphaned at a young age, and between that and the Soviet’s early anti-religious campaigns had almost no Jewish education. Kogan’s mother, on the other hand, was the daughter of Rabbi Yosef Tamarin, a staunchly religious Jew who had studied at the yeshivah of Rabbi Yisrael Meir Kagan (renowned as the Chofetz Chaim) in Radin, Poland, before forming a relationship with the Sixth Rebbe in Leningrad in the 1920s.

It was Kogan’s grandfather who first instilled in him a love for his heritage. “On Chanukah I remember him telling me, ‘Izyanka, look under your pillow,’ and there would be Chanukah gelt lying there,” Kogan says. But tragedy in the Soviet Union was never far. In 1950, Tamarin became the subject of KGB harassment for his role in Leningrad’s matzah-baking efforts. After one of a series of day-time interrogations, he stepped out onto the street, collapsed and died. At his funeral, Rabbi Moshe Mordechai Epstein (Pinsky), the elderly, unofficial Chassidic rabbi of Leningrad and a graduate of Chabad’s Yeshivas Tomchei Temimim, extracted a promise from Kogan’s parents that they’d remain religious Jews, just like the family patriarch.

Kogan’s grandfather was the only family member who was truly knowledgeable about Judaism, and it might have been expected that his death would mark the end of Jewish tradition in the family, as happened in so many other Soviet Jewish families. Instead, Kogan’s parents kept on observing despite their own relative lack of Jewish knowledge, something he credits to a blessing his grandfather received from Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak.

“Before the [Sixth] Rebbe left Russia in 1927 [following his imprisonment by Soviet authorities], he called my grandfather into his room,” Kogan explains. “He told my grandfather: ‘Ayere kinder bleiben mit,’ ‘Your children will remain Jewish.’ ”

Kogan grew up knowing of the Sixth Rebbe’s blessing, but there was more.

“From a young age, my mother would tell me that in the world there is a Lubavitcher Rebbe—she didn’t even say Lubavitcher, she would just say Rebbe—who worries about all the Jews in the whole world,” Kogan explained to Jewish Educational Media’s (JEM) My Encounter with the Rebbe oral history project. He might not have understood the exact meaning of his mother’s words, but he remembered them.

As soon as Kogan began attending Soviet public school, his parents hired the first of a string of melamdim, Jewish religious teachers, to come to their home. They were all old men, members of a generation that had still received a traditional Jewish education, and they taught the Kogan boys basic Jewish knowledge. Each melamed—Kogan can list them all—made some kind of impact on the children.

There was, for instance, R’ Avraham Abba Estrin, the longtime shames of the Leningrad synagogue, who taught Kogan and his brother the morning blessings, the Shema and Shmoneh Esreh prayers. Though still a child, Kogan understood that he was not to display any familiarity with Estrin when he saw him in the synagogue. “No one was supposed to know that he taught me,” he explains.

It was not only what the old men taught Kogan that he absorbed, but what they left unsaid. Each of them, without exception, had suffered for their beliefs at the hands of the Communist regime. Another teacher, R’ Berel Medalia, was the son of Rabbi Shmarya Leib Medalia, a Lubavitcher Chassid who served as chief rabbi of Moscow before being arrested and executed by Stalin in 1938; three of Rabbi Shmarya Leib’s sons were likewise arrested. Berel Medalia served something like a decade in the Gulag system, returning a broken man, and by the time Kogan knew him, he lived alone in a room in the Leningrad synagogue. Despite everything, in addition to teaching children like the Kogans, over the years Medalia became a quiet Jewish influence on many young refuseniks (A Russian-language article about Berel Medalia can be seen here.)

In fact, during the years Kogan was growing up there was almost no significant figure in Leningrad Jewish life who had not served time behind bars or barbed wire. The city’s official chief rabbi, Avraham Chaim Lubanov, who also came from a Chabad background, had served two separate sentences, coming out the second time not long after Stalin’s 1953 death. Epstein, the unofficial rabbi, was arrested not long after his moving exhortation at Kogan’s grandfather’s funeral, only returning around 1958.

The Kogan boys’ early Jewish education was bareboned. The old men taught them to read and memorize, but did not delve much into the meaning of the holy words. This changed for Kogan in late 1958 or early ’59, when a new teacher named R’ Michel Rapoport began preparing him for his bar mitzvah.

“R’ Michel’s … the one who began translating all of the words [for the first time],” Kogan told JEM. “From that point on, I started understanding what Shema Yisroel meant, what Shemone Esreh was, the words, the meaning, all of it.”

Rapoport was likewise a graduate of Tomchei Temimim, the institution founded in 1897 by the Fifth Rebbe—Rabbi Sholom Dovber of Lubavitch (1860-1920)—to be the vanguard of Jewish resistance in the bloody 20th century. Rabbi Sholom Dovber’s son and successor, the Sixth Rebbe, had carried his father’s work into the Bolshevik era, overseeing the creation of dozens of clandestine branches of the yeshivah as part of his USSR-wide Jewish educational network. If anyone epitomized the methods, goals and efficacy of the Tomchei Temimim vanguard, it was Rapoport. Beginning around his bar mitzvah in 1927, Rapoport had been educated in various branches of Tomchei Temimim, from Kremenchug, Ukraine, to Vitebsk, Belarus, to Baku, Azerbaijan. In 1936, as Stalin clamped down further on every semblance of free thought and expression, the 22-year-old Rapoport was appointed to lead Tomchei Temimim in Kursk, Russia. In 1938, following a 19th of Kislev farbrengen gathering in Kiev, he was arrested and served eight years in prison and the Gulags.

He came out, got married and settled in Leningrad. Then, in 1950, the authorities arrested his wife, Sara, and a few months later re-arrested Rapoport. The couple were freed around 1958-’59 and returned to Leningrad, where their son, a childhood friend of Kogan’s, had been living with his grandfather since he was a toddler. Having served some 17 years in all, Rapoport was back in Leningrad and once again teaching Torah to children.

As Kogan’s bar mitzvah approached in the summer of 1959, his mother feared the ceremony would summon unwanted interest from the authorities, and turned to the recently released Epstein for advice. Epstein instructed her to hold the bar mitzvah in a small summer vacation town outside Leningrad. “He also said that Papa shouldn’t be there,” Kogan explains. “Instead of my father, Rav Epstein made the Baruch Shepetarani [the blessing a father recites at his sons’ bar mitzvah].”

Kogan continued studying Torah with R’ Michel until the Rapoports were able to leave for Israel in 1971.

Refusenik Days

In 1967, while studying in the Leningrad Electrotechnical Institute, Kogan married his wife, Sofya, who’d remain his life partner until her passing in 2009. For a time, Kogan worked as a systems development engineer focused on automation and control. When he learned that the enterprise where he worked was sending their systems to the Soviets’ allies (and Israel’s enemies) Syria and Egypt, he decided to apply for permission to leave the USSR. The Kogans were both immediately fired from their jobs—Sofya was a dentist—and their 14-year-long quest for Soviet exit visas commenced.

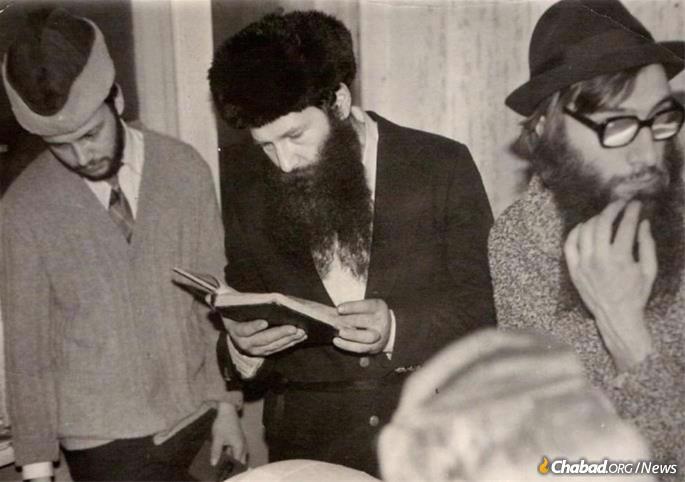

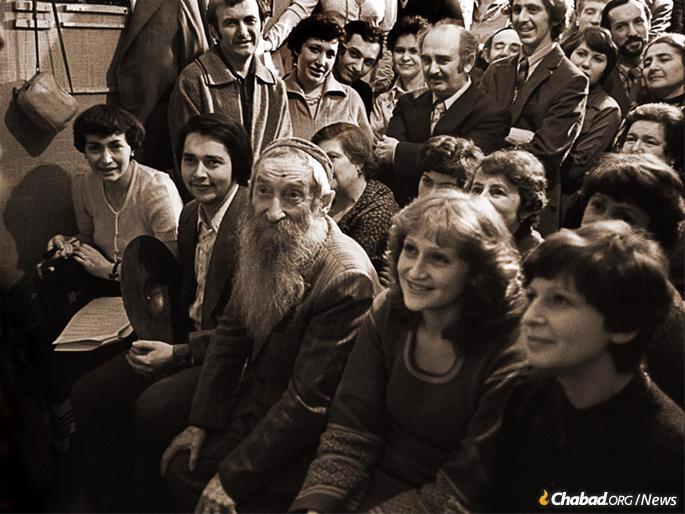

Refuseniks inhabited a twilight zone of sorts. On the one hand, they had to contend with both the repeated disappointment of being told they could not leave the Soviet Union, as well as the social and economic repercussions of outing themselves as anti-Soviet elements. On the other hand, refuseniks created their own communities, supporting each other materially and spiritually. The Kogans jumped into this new world, and their apartment became a center for Leningrad Jewish life.

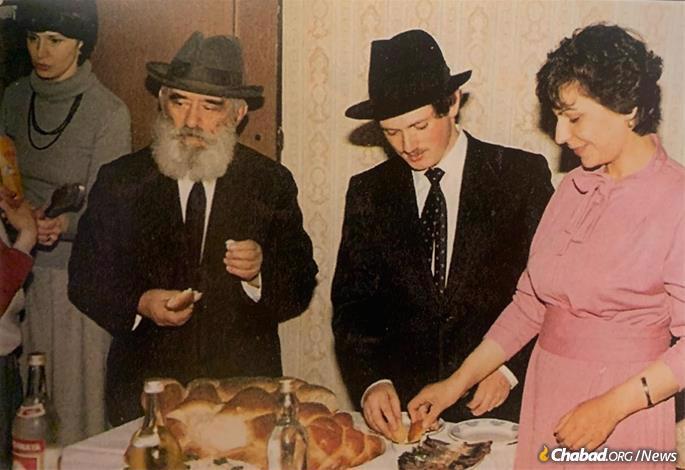

Among the many young Jewish refuseniks who credit the Kogans’ assistance on their path to Judaism were Lev and Marina Furman, who first connected with them in 1974. They would recall joining about 50 others at the Kogans’ apartment for their first kosher Passover seder. Other communal activities at the Kogan home included Hebrew and Jewish study circles and Purim spiels.

The Kogans also worked for the material benefit of their brethren. After the KGB banished refusenik Ida Nudel to a remote Siberian village in 1978, Kogan and a number of young people in his growing circle traveled to the village to bring her food and renovate the drafty hut where she lived. When Nudel fell ill in 1980 and was denied adequate medical care, Kogan and Sofya, pregnant at the time, set off once again for Siberia. They traveled on one of the last barges navigating the River Ob before the winter frost, and Sofya, with her medical background, was able to help her.

Another dissident whom Kogan became involved with was Yosef Mendelevich. As Mendelevich began his 11th year behind bars, word came out that the KGB had confiscated his homemade tzitzit and Jewish books, and he’d begun a hunger strike.

“I fasted for two months, only drinking water,” Mendelevich told me recently. “The case was passed on secretly to the refuseniks, and that’s how Reb Yitzchak got to know about it.”

Around the same time the Rebbe’s emissary from America, Rabbi Berel Levy, visited Leningrad, and recorded footage of refuseniks addressing the Rebbe, which was later played for the Rebbe in New York. When his turn came, Kogan asked for a blessing for all the Jews behind bars in the Soviet Union, with Mendelevich particularly in mind.

“He passed the story to the Rebbe, asking that the Rebbe should work to limit my hunger strike and get me out of the camp,” Mendelevich remembers. “After 60 days of the fast, my jailers unprecedentedly returned me the books. It was on Chanukah. A Chanukah miracle! Less than two month later, I was expelled by the Soviets and sent to Vienna.”

Mendelevich was released from prison on Feb. 18, 1981: Purim Katan. Kogan heard the news while listening to BBC on his shortwave radio. At that moment he recalled his mother’s words—that the Rebbe cared and worried for Jews wherever, quite literally—they found themselves in the world.

‘Why Don’t You Learn?’

By 1979, Leningrad had been without a practicing shochet (ritual slaughterer), and thus without kosher meat and poultry, for two years. Around that time, R’ Mottel Lifshitz—a Lubavitcher Chassid and likewise a Gulag survivor who served as Moscow’s official shochet and mohel—visited Leningrad. “R’ Mottel, please, my children haven’t eaten meat or poultry in two years,” Kogan told him. “Let me find something for you, a few chickens, a lamb, anything, and shecht it for my family!”

Lifshitz demurred. According to the Soviet’s rules, he was not allowed to slaughter kosher food outside of Moscow, and if someone were to inform on him, it could place Moscow’s own kosher supply at risk. “Izya, you’re young, why don’t you learn?” Lifshitz suggested.

Kogan began studying shechita with an elderly Chassid living in Leningrad, who agreed to teach him on the condition that he never reveal his name to anyone. “He was a Chabad Chassid, that’s all I’ll tell you,” Kogan says. The study was intense, up to eight hours a day. When they finished, the old man granted Kogan hoda’ah—that is, the test administered by a shochet. Yet he was still lacking kabbalah, the certification that can only be granted by an ordained Orthodox rabbi. Thus on each shechita run that followed, Kogan needed a fully-certified shochet to supervise him.

For the next year or two, Kogan would shecht only when accompanied by one of two old men—“eltere Chassidim” he refers to them as—R’ Naftali Hertz Chidekel or R’ Rafael Neymotin, both graduates of Tomchei Temimim living in Leningrad. After Kogan learned how to shecht beef, he’d also carry the 200-pound calf carcasses up eight flights of stairs to Chidekel’s apartment for nikur, or de-veining. “It was most difficult for Sofya,” Kogan adds. “Do you know what it’s like to soak and salt an entire cow in your apartment kitchen? A doctor, and she’s salting cows!”

Kogan grew especially close to Neymotin, who became like his spiritual father. R’ Refoel’s “character [was] tempered like steel through years of exile as an unyielding warrior for his faith, a philosopher and wise elder,” Kogan wrote in the foreword to Irina Ospiova’s Russian-language Hasidim: Save Thy People (Moscow, 2002). “I learned literally everything from this man, a Chassid to the marrow of his bones.”

Neymotin spoke only Yiddish with Kogan, reawakening the language within him. “R’ Refoel would never say treif[unkosher],” Kogan says to illustrate Neymotin’s deeply Chassidic form of teaching him. “If something wasn’t right, he would say, ‘Nit far unz [not for us].”

Kogan eventually grew tired of dragging the old men around Leningrad and decided to hang up his knife. Neymotin was adamantly against this, and referred Kogan to another of Rabbi Shmarya Leib Medalia’s sons, Rabbi Avraham Medalia. This Medalia, a math professor and a Torah scholar who had been ordained in his youth, was also a Gulag survivor, and in the late 1970s began taking on more rabbinical responsibilities in Leningrad. “Reb Refoel told me about your problem,” Medalia told Kogan, “shecht a few chickens in front of me and I’ll watch.” Medalia then told him he would not write out the kabbalah certification on paper seeing as he had already spent enough time in the Gulags, but if anyone had any questions they could call him. Levy, the Rebbe’s emissary from the United States, would eventually give Kogan a written certificate.

Now that Kogan could shecht on his own, he could also train new shochetim, and he started an underground yeshivah for kosher slaughter. One of Kogan’s last projects before leaving the Soviet Union was preparing his last 12 students to be tested by a rabbi visiting from America.

Doing More

Though the KGB had told Kogan he’d never receive an exit visa due to his science and engineering background, permission came in the winter of 1986. A few weeks later, they were in Israel, and a few weeks after that in New York. At about 6:50 p.m. on their first day in Brooklyn, the couple was ushered into the hallway outside of the Rebbe’s office, where three chairs had been set up.

“We walked in and the Rebbe said ‘Please sit,’ ” Kogan recalls. “We knew that Chassidim don’t sit in front of the Rebbe, so we stood. The Rebbe asked us again, but we remained standing. Then he said ‘I know you were told not to sit, but it will be more comfortable for me if you sit because our conversation will be a long one.’ At that point, we couldn’t stand anymore.”

Kogan first handed the Rebbe a full written report, and when they sat down the Rebbe began asking about every detail of the exit process and the departure. The discussion then moved on to Jewish activities in Leningrad. At one point, the Rebbe asked about the women’s mikvah in Moscow’s Marina Roscha synagogue, and Kogan replied that he was sure the Rebbe had heard that the KGB had cemented it closed. “The Rebbe asked me if there is a separate entrance there for women, and I said I didn’t know the answer to that,” he says. “Later, when I walked out, I called Dovid Karpov in Moscow and he told me there wasn’t a separate women’s entrance, but he could build one quickly through an adjacent office. As soon as they did that, out of nowhere the authorities came back and said, ‘Are you going to dig the mikvah out yourselves or should we do it?’ You see how the Rebbe saw it.”

The Rebbe told the Kogans that Jews in the Soviet Union needed to know that protesting in the streets was not the most important thing, but that their focus ought to be learning and leading a Jewish life, with an emphasis on providing their children with a Jewish education. At the same time, those who had already emigrated from the USSR should recognize that it is not enough to just reach Israel or the West, but that they need to continue on their journey towards Torah and mitzvot. (Some of these details can be gleaned from contemporaneously written diaries of what Kogan later shared with the gathered crowd.)

During their meeting, the Rebbe reiterated his opposition to protests, stating that it was an especially sensitive moment as there were great internal changes taking place in the Kremlin. “The government wants to change,” the Rebbe told Kogan in Yiddish, “it must not be disturbed.”

“We had just left the USSR with great difficulty, but here we were and the Rebbe was telling us that Jews will soon be leaving the Soviet Union without limits, and we need to start preparing to welcome them and preparing things for them in Israel,” Kogan adds. Rather than attempting to manage geopolitics and the Kremlin’s inner workings, the Rebbe wanted Kogan and his fellow activists to focus on the concrete areas where they could and would make a real difference. “That remains as true today as it was then,” he says.

In the beginning of the conversation, the Rebbe had noticed that Sofya Kogan was uncomfortable with Yiddish and switched to Russian. (During the audience, he also told the Kogans they should not let their Russian language falter, as they’d need it in the future.) Two hours later, after the Rebbe had outlined what he saw as the Kogans’ work in Israel, the couple rose to leave.

“My wife, of blessed memory, was quiet, very refined,” Kogan explains. “Suddenly, she bursts out, in Russian: ‘Rebbe, we’ll do everything in our power!’”

The Rebbe smiled and said, in Yiddish: “Ah Chassid tut mehrer vi ehr hot koichos—A Chassid does more than in his power.”

It’s this idea that more than anything else is the lesson for the day, says Kogan. The entire Soviet Jewish story, the self-sacrifice—of Chassidim, of old Jewish men and women, of young Jewish zealots with fires burning in their hearts—was never governed by the rules of nature. Their power to succeed came not from the natural order of things but from the supernatural, from the transcendent. This was true then and remains true today. There are natural limits to an individual’s abilities, but he or she must always do more.

At age 75, R’ Yitzchak Kogan shows no signs of slowing down. He continues to shecht and teach shechita, while inspiring and leading his Moscow community. After all, the Rebbe told him to stay in Russia as long as he has strength, but also empowered him to reach beyond his own natural abilities.

“I carry the Rebbe’s words with me right here,” he says, “on my heart.”

This article has been reprinted with permission from chabad.org