The Rhyme and Rhythm of Chassidic Life Through Chassidic Song

by Mendel Super – chabad.org

Many a participant and observer of Chabad life has been transfixed by the melodies and strains that punctuate, and indeed uplift, the everyday life of a Chassidic community. The often wordless melodies dictate the mood and set the tone of an event, whether a meditational niggun (“melody”) during prayer, a march of victory at the conclusion of Yom Kippur or the haunting tune that accompanies Chabad brides and grooms to the wedding canopy, niggunim permeate every facet of Chabad life.

In Performing Chassidishkeit: Spirituality and Identity Construction in Chabad Nigunim—a presentation on Zoom recently hosted by the Jewish Music Forum, the scholarly arm of the American Society for Jewish Music—ethnomusicologists Dr. Michel Klein and Dr. Ellen Koskoff discussed the role niggunim play in constructing the contemporary Chabad identity.

Klein hopes that the audience developed a feel for the richness of Chabad niggunim and a unique view into the “powerful role that niggunim play in our lives.” He focused on an all-encompassing facet of niggunim in contemporary Chabad life. “Niggunim are used to construct and express identity,” Klein tells Chabad.org.

“Our identity is based on what we surround ourselves with—what we listen to, the way we dress, the way we talk, where we live, what we learn, who we interact with … all those things. By listening to and performing niggunim,we reinforce that feeling of being connected, of our Chassidic identity and to connect with the broader Chabad community as well as to the Rebbe [Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory].”

Koskoff, author of Music in Lubavitcher Life, published in 2001 after three decades of research, recalled her experiences documenting the music of Chabad Chassidim at the farbrengens of the Rebbe at Chabad-Lubavitch headquarters at 770 Eastern Parkway and inside Chabad homes in the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn, N.Y., and on the street. Koskoff noted how with niggunim, Chabad Chassidim—living in the relative peace of the 21st century—can “attach themselves to their forebears who lived in the shtetl” amid persecution and decimation of their way of life.

‘Song Is the Pen of the Soul’

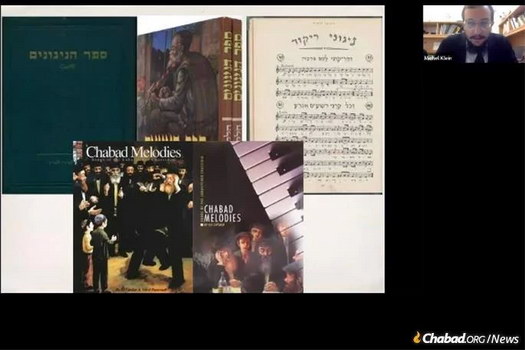

The production and notation of music have long been a focus in Chabad circles. Nichoach, a musical society established at the behest of the Sixth Rebbe—Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, of righteous memory—pioneered the revival of these centuries-old songs by producing records in the classic songs of the Lubavitcher Chassidim vinyl albums and notating them in the two-volume Sefer Haniggunim collection, first published in 1949, and a best-seller until today.

Musically, Chabad melodies use the conventional Western pitch set (also known as diatonic pitch set) unlike some Oriental Jewish music set in the Eastern pitch set, which uses the less common quarter tones. On a more specific level, Klein observes that Chabad melodies are often set within the harmonic minor scale and the Ukrainian Dorian scale, lending them a particularly pensive flavor.

But it’s more the stylistic performance that makes a song a niggun. “A niggun just sung in a very straightforward way can be dry and lifeless,” says Klein. “What imbues it with life and inspiration is the unique style that Chassidim sing it in and that gives it its Chassidic flavor.” Elements such as ornamentation, inflection, tone and even physical gestures, such as clapping or drumming on the table, bring the niggun to life, Klein adds.

Klein explains the difference between various modes of music in spiritual terms. “Music is a spectrum; there is music that lifts one up and music that drags one down. The sole purpose of Chabad niggunim is to elevate and uplift.” Another element he points to is the identity of the composer. The third Rebbe of Chabad-Lubavitch—Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Lubavitch (known as the Tzemach Tzedek)—taught that when one sings a song, their soul unites with the highest level of the composer’s soul. “Chabad niggunim are composed for Chassidim, by the Chassidim and Rebbes,” notes Klein.

“If words are the pen of the heart,” taught Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, “then song is the pen of the soul.” Klein explains this saying by noting that the spiritual narratives of Chabad Chassidic thought are expressed by singing niggunim. Quoting the 19th-century Chassidic master Rabbi Hillel Paritcher, Klein explains that in Chabad, niggunim and Chassidic philosophy are intertwined, partners in a symbiotic relationship. “One who has no chush (‘feeling for’) in neginah (‘music’),” Rabbi Hillel explained, “has no chush for Chassidus.”

The niggun’s spiritual calling is personal for Klein. The 33-year-old was raised in a traditional Jewish home in Middletown, N.Y., though the family wasn’t observant. “I always had a positive relationship with Judaism,” he notes, but it wasn’t until he went off to Ithaca College and connected with Chabad at the nearby Cornell University campus that he began taking Jewish practice seriously.

Klein recalls going to a farbrengen on Shabbat at the campus Chabad led by Rabbi Eli and Chana Silberstein. There,they were singing niggunim. The heartfelt melodies were unlike anything he’d heard before. “They really inspired me. From that Shabbat onward, I gave up eating meat and dairy together; I gave up pork and I gave up shellfish.”

That was his sophomore year. By the next year, Klein was only eating kosher meat and wearing a kippah. At the same time, he played the organ for a church and was a music director in a theater that performed on Shabbat. “I was wearing a yarmulke, learning Torah, and it pained me. ‘Maybe I shouldn’t play on Shabbos. Maybe I shouldn’t be playing in a church; church isn’t a place for a nice Jewish boy.’ ”

He gave up his dream of being a music director and composer for musical theater. Then he committed to keeping kosher, all the way. But he wanted more. He took a year’s break and went to study at the Mayanot Institute of Jewish Studies in Jerusalem. “I’m going to yeshivah, I’m not going to focus on music here,” Klein told himself. But he found himself composing Jewish music in his free time and learning more niggunim. “It was in my neshamah (‘soul’).”

Klein returned to the United States and continued his Jewish education at Tiferes Bachurim, in Morristown, N.J. After meeting his wife, Noa, getting married and living in Crown Heights for a while, he went back to graduate school at UCLA, writing his dissertation in Chassidic music.

“Niggunim are not just for Chabad Chassidim; they’re for everyone,” reflects Klein. “The spiritual power of a niggun can really awaken you—and that’s what it did for me.”

This article has been reprinted with permission from chabad.org