Obituary: Rabbi Fabian Schonfeld, 97, National Rabbinic Leader

by Mendel Super – chabad.org

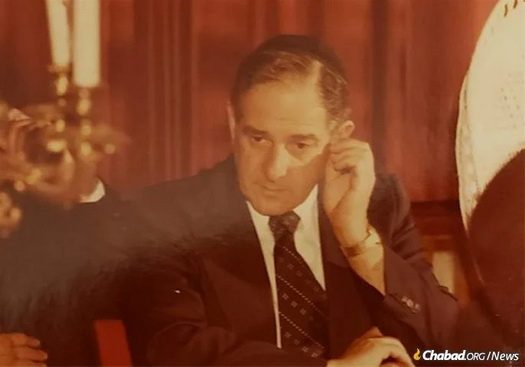

He lived in two distinct worlds—that of Old-World, pre-war Poland, where he was deeply influenced by Chassidic rebbes, and that of modern, post-war America, where he became a foremost disciple of Yeshiva University’s Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik. For Rabbi Mordechai Shraga Schonfeld, known as Fabian in English, who passed away last month at the age of 97, blending these two approaches to Judaism wasn’t a balancing act; it was simply his way of life.

Born in Zawiercie, Poland, on Dec 14, 1923, to Shabse and Malka Bluma (nee Oksenhendler) Schonfeld, his family moved to Vienna, Austria, as an infant, where they remained until 1938. Schonfeld’s father was the secretary of the World Agudah, which represented much of Eastern European Orthodoxy and editor of its Hebrew-language weekly newspaper, HaDerech. As such, the young boy grew up surrounded by some of the most prominent rabbinic leaders of the day, where he had firsthand exposure to activism and leadership.

Shabse Schonfeld’s involvement in the Jewish community was well known. He was on the Gestapo’s list and in 1938, when they marched into Austria, they came looking for him. Shabse Schonfeld had the foresight to escape to Czechoslovakia alone, while his wife and children left Vienna in the summer of 1938.

After smuggling themselves across the French border, from Luxembourg, by bribing a guard, Fabian and his brother attended a Parisian Jewish school. It was in Paris that they received their visas for England—Shabse Schonfeld was already in England at the time and procured the papers with the help of British Rabbi Solomon Schonfeld (no relation), an unsung hero of that dark era who boarded a train to Vienna in the wake of Kristallnacht and saved 300 of Vienna’s Orthodox youth.

Fabian and his brother were part of the Kindertransport—the operation that saved around 10,000 Jewish children and teenagers from the Holocaust. Many of these children were the sole survivors of their families, but Fabian was one of the lucky ones; his parents had both escaped to England before it was too late.

As a young Jewish refuge in England, Schonfeld rode out the war in the sleepy village of Shefford, where an entire Jewish school was evacuated to as part of the British government’s “Operation Pied Piper,” which saw thousands of schoolchildren and their teachers evacuated to towns across the English countryside in anticipation of the German aerial blitzes over the London skies.

In 1946, he married Shaulit Jacobovitz, a sister of future Commonwealth Chief Rabbi Lord Immanuel Jacobovitz. In 1950 the couple moved to the United States, where Schonfeld studied for his rabbinic ordination under Rabbi Soloveitchik.

Schonfeld hadn’t always envisioned a path in the rabbinate; in the United Kingdom, he had been a soccer coach—not the typical pre-rabbinic training. His father-in-law, Rabbi Julius Jacobovitz, didn’t think the young man would make a great rabbi. But Shaulit did. She saw somewhere within her husband the rabbinic potential. “He’ll be a great leader someday,” she told her father.

While studying for his ordination, Schonfeld worked as a youth director in a New York synagogue and taught at Yeshivah Zichron Moshe in the Bronx. At that time, recognizing the talent that the rabbinic scholar displayed, he was offered a position as rabbi in a large congregation in Worcester, Mass.. He turned it down in favor of a new, unheard-of synagogue that barely brought together a minyan in a basement in Kew Gardens Hills, a neighborhood in Queens, N.Y., much to the bewilderment of the Yeshiva University faculty.

Time proved the intuitive young rabbi right. From a small core group in 1953, when Schonfeld assumed the rabbinate, the congregation—later named Young Israel of Kew Gardens Hills—numbered 800 members by 1955.

Sadly, Shaulit passed away just years later in 1959. In 1961, he married Ruth Leifer, nee Schindelheim.

Maintained Warm, Personal Relationships With Congregants

Much changed in the world during the six decades of his rabbinic career, until his retirement in 2011, but the rabbi remained committed to his timeless, “old-fashioned” values of respect, decency and loyalty. He was loyal to rebbes of the Gur Chassidic dynasty, of which he considered himself a follower, and to his beloved teacher and mentor, Rabbi Soloveitchik. His loyalty to his congregation was fierce. “In the 1970s, he was offered a position elsewhere for double the salary,” his son and successor, Rabbi Yoel Schonfeld, told Chabad.org. “He turned it down.”

The philosophy that drove his success in the rabbinate was simple: “Rabbis make a mistake,” he taught his son. “They think they will succeed in their congregation by being internationally renowned. The congregant in shul wants to know, ‘Did you visit me in the hospital?’ They don’t care about your ‘scholar-in-residence’ in Detroit.” True to his words, the rabbi maintained a warm, personal relationship with every one of his congregants. “When a member had a simcha in the family, he would give them a handwritten card with his good wishes,” says Rabbi Yoel Schonfeld. “Each Friday, he would call tens of widows, wishing them a ‘Good Shabbos.’ ”

Money meant little to him. “He provided kosher certification to a local grocery under the name Young Israel of Kew Gardens Hills. He never charged them for it; he felt that the community needs its own kosher certification,” recalls his son. “After his passing, we found decades worth of uncashed checks.”

His leadership extended far beyond his Queens home. Schonfeld was heavily involved in the national Orthodox organizations. He was the president of the RCA, the Rabbinical Council of America; president of Yeshiva University’s Rabbinical Alumni association; played many roles in the Young Israel movement; led the Orthodox Union (OU) kashrut division; and served as chairman of Poalei Agudas Yisrael of America.

His local involvement led him to establish the Queens Vaad Harabbonim, or rabbinical council, while owing to his prominence on the national stage he gave the invocation at the 1984 Republican National Convention in Dallas before President Ronald Reagan.

“We pray that the evil of bigotry, prejudice, racial hatred and anti-Semitism, so strongly condemned by this convention, will be eradicated from the hearts and minds of all mankind,” he intoned, with his British-tinged European accent. “ … In the words of Isaiah, ‘Nation shall not lift sword against nation, and teach war no more.’ We pray for the strength and stability of our country, that it may continue to be a champion of freedom and a beacon of hope to all peoples on earth, and let us say, Amen.”

Schonfeld developed a deep admiration and respect for the Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—with whom his teacher, Rabbi Soloveitchik, had a close relationship going back to their years together in Berlin.

“In many ways, the Rav [Rabbi Soloveitchik] fostered my later attachment to Chabad-Lubavitch,” Schonfeld told JEM’s My Encounter project in an interview, “because in every major lecture that he gave, he always quoted the writings of the Baal HaTanya, Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, the 18th-century founder of Chabad. He urged his students to study the Baal HaTanya, especially before the High Holidays, and he voiced his great admiration for Lubavitch philosophy and wisdom, as well as his great respect for the Rebbe.”

Schonfeld first met the Rebbe in person when he was elected president of the Rabbinical Council of America in 1974. Together with a delegation of RCA leaders, he met with the Rebbe several times for private audiences, sometimes alone as well.

He was taken by what he saw as the Rebbe’s revival of Judaism after the Holocaust and enamored with the work of Chabad’s emissaries worldwide. He would vigorously defend Chabad-Lubavitch for any criticism he overheard.

Rabbi Soloveitchik recounted many details of his years with the Rebbe in Berlin to Schonfeld; these memories form much of what is currently known about that period of the Rebbe’s life, as the Rebbe didn’t speak much about his own life.

In a decidedly non-Chassidic environment, the Rebbe was an anomaly. “[Rabbi Soloveitchik] also told me that the Rebbe never once failed to begin his day by immersing in the mikvah, the ritual bath. The Rav was very impressed by this—that the Rebbe was able to stay committed to Chassidic ways even in the midst of that secular environment.”

The Rebbe moved on to Paris, while Rabbi Soloveitchik completed his university studies and settled in America in 1932. When the Nazis invaded, the Rebbe and his wife, Rebbetzin Chaya Mushka, fled to Nice, France. So did Schonfeld’s stepmother’s father, Wolf Reichman, a Belzer Chassid.

“Wolf Reichman fled to Nice with his family and,” Schonfeld told JEM, “as Passover was approaching, he was worried where he was going to get matzah. After much trouble, he found a farmer somewhere who was willing to sell him wheat, which he planned to grind himself. He would have to make the oven kosher and oversee the baking, and all this was causing him a great deal of worry.

“As he was sitting there worrying, he heard a knock at the door, and was surprised to find standing on his doorstep a bearded young man sporting a French beret. The young man said, ‘I hear that you are thinking of baking matzah for Passover. If you succeed, please let me know because I also need matzah.’ Wolf Reichman agreed and promised to contact him.

Before he could, however, the young man returned with a parcel in his hands. He said, ‘I came to you a few weeks ago about the matzah. In the meantime, I was able to find wheat, grind it and bake it. And since you were willing to share your matzah with me, I want to offer you some of mine.’

This young man’s name was Menachem Mendel Schneerson—this was the future Rebbe. What impresses me about this story is that he didn’t forget about Wolf Reichman and, even though he no longer needed the matzah, he took the trouble to return and share what he had baked.”

In 1991, Schonfeld needed the kind of help that a Chassid turns only to a Rebbe for. His daughter was in her 20s, and she and her parents wanted her to get married. But a suitable match wasn’t found, and this caused them some worry. Schonfeld approached the Rebbe for a blessing.

The Rebbe handed him two dollar bills, instructing him to give one to charity when his daughter gets engaged. “The dollar was lost,” recalls Rabbi Yoel Schonfeld, “and she didn’t get engaged that year.” The next year, Schonfeld returned. The Rebbe handed him a dollar, but Schonfeld remained standing there. “Last year I asked the Rebbe for a blessing for my daughter to get married … could the Rebbe give her a blessing?”

“But I gave her a blessing last year!” the Rebbe replied. “Yes, we are still waiting for the blessing to be fulfilled,” answered Schonfeld. “I had higher expectations of myself,” said the Rebbe, “at least from now on may you have good tidings. Give this to charity for your daughter again, may you have good news, and very soon.”

“It didn’t take long,” Schonfeld told JEM, “ … A few weeks later, she was engaged. Was it a miracle? I don’t know. That’s what the Rebbe said … the second dollar did it.”

Schonfeld is survived by his wife, Ruth and their children: Aviva Pinchuk, Rebbetzin Vicki Berglass, Debbie Wolfe, Yossi Schindelheim, Rabbi Yoel Schonfeld, Phyliss Schwartz, Debbie Spero, Georgette London, Rabbi Yehuda Aryeh Schonfeld and Tamar Koppel.

This article has been reprinted with permission from chabad.org