To Understand Yud Daled Kislev

Vinek is the name of the nice Pole who took Devora and me on last Motzai Shabbat through the streets of Warsaw. Vinek is a wise man, about 55 years old, who understood pretty quickly that serving as a driver for Jews in Poland could provide him with a good living. I saw that he understood his clientele quite well when I got into the Toyota Sienna that he had imported privately from New York. “The chassidim from America love this car. I bought it from a Jew in Boro Park. Look – it even has a sticker with a holy text in Hebrew”, he said, pointing to a Tefillat Haderech (prayer for the traveler) sticker appearing on one side of the windshield.

Vinek knows what each traveler is looking for – who wants to see the remains of the ghetto, and who wants to view the cemetery or any other noteworthy place in Poland, which, as is known, is full of Jewish graves.

When Rav Shalom Ber Stambler introduced us to him and told him to take us to the places that the Chabadniks want to see, Vinek understood very fast.

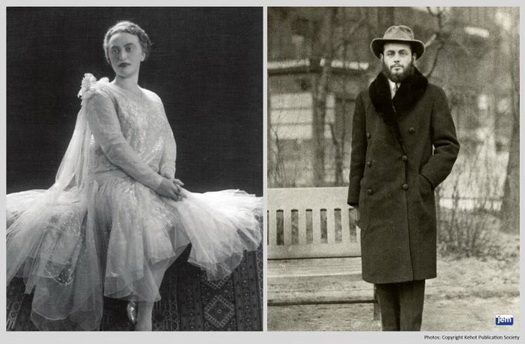

There are two such sites in Warsaw. One is the place where the wedding of the Rebbe and the Rebbetzin, took place. “Zhe hupeh”, as he puts it, is actually a yard of a residential building that has replaced the Chabad yeshiva in Warsaw. There, the chuppah of the Rebbe and the Rebbetzin took place on 14 Kislev 5689 (1928), today, ninety-one years ago. From there he takes his Chabad tourists to another street, where the wedding meal hall used to be.

Vinek does not understand why we are so excited about standing and sometimes dancing as well near a place where something once stood and today is no longer. I can assume that not only Vinek doesn’t understand – plenty of other people with heads on their shoulders don’t understand us either. But we don’t have to explain anything. We know that in this place Hashem prepared the salve for the wound. Here Hashem planted the seeds of the revolution in Jewry that the Rebbe brought about, twenty years and one war later.

The 19th of Kislev, 5689 (1928), a few days after the wedding, and they were already in Riga, still in their Sheva Brachot week. The father of the bride, the previous Rebbe, turned to his secretary, R. Chatche Faigin, and asked him to please send a telegram to a chassid who lives in Rostov, where his father, Rabbi Shalom Dov Ber, the fifth Chabad Rebbe, was buried. “Ask that someone there read the telegram that I will dictate to you on his grave,” he requested. The content of the telegram consisted of only three words in Russian: “His will was done.” But my father explained to me once that the translation should be “His desire was done.” Meaning, that the Rebbe, The Rashab, very much wanted this shidduch to take place, that the son of Rabbi Schneersohn of Yekatrinoslav should marry his granddaughter.

While I was still in Vinek’s Sienna, I thought that the mailman of Rostov who delivered the telegram containing three Russian words probably did not understand what it was that he was delivering. The Soviet Union was in the midst of Stalin’s somewhat insane arming of the U.S.S.R. and industrialization projects. The rest of the world, and especially the United States and Germany in its wake were facing the beginning of the Great Depression of 1929. The world was being shaken up – above the surface and below. What meaning could there be in three Russian words being transmitted from Latvia to Russia, from Riga to Rostov?

But several years passed. The world in general underwent a deep shock and the Jewish world came close to being destroyed. Throughout the world, Jews preferred to forget about their Judaism. To be a Jew during this period was a burden. The common expression used by people was “It’s hard to be a Jew.” And precisely at that time those three words in the telegram from twenty years ago surfaced. The dream became a reality. The young man from Yekatrinoslav took upon himself the leadership of Chabad Lubavitch, continuing the same task of his father-in-law the Rebbe, and realized the purpose of his father-in-law’s father, the Rashab of Rostov.

The young man became the most famous and the most influential Jewish personality in the Jewish world after the Holocaust, an influence that continues to this day – an influence of good deeds, chessed (loving-kindness). An influence of Jewish pride wherever a Jew might be.

So nice Vinek doesn’t understand, and a few other people also do not understand. But I know that I stood in the place where the seeds of the revolution were planted: No longer a heavy, sad Judaism; no longer shame and burden, but rather happy Judaism, happy Jews. It is not hard to be Jew. It is joyful and good to be a Jew.