Obituary: Rabbi Chaim Ciment, 90, Boston Educator for Nearly Seven Decades

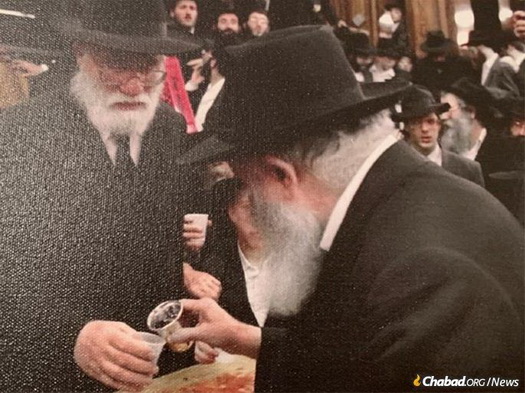

by Mendel Super – chabad.org

Rabbi Chaim Ciment, an imposing fixture on Jewish Boston’s scene for the last seven decades, passed away on Sept. 26 at the age of 90.

Sent to Boston by the Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—in late 1953, he joined the Jewish studies faculty of what was then known as the Boston Lubavitz Yeshiva—Achei Temimim Jewish day school. In the late 1960s Ciment was appointed executive director of the yeshivah, right around when it was renamed New England Hebrew Academy—Lubavitz Yeshiva (NEHA). The name change wasn’t a rebrand, but rather a reflection of the yeshivah’s growing central role in providing a solid Jewish education for children in the entire region, and was the mission Ciment dedicated his life to. Under his leadership, the school established a preschool, elementary school, high school and a yeshivah gedolah rabbinical college.

Combining a physical height and strong presence with a single-minded devotion to the mission at hand, there was little that could stand in Ciment’s way. But his students also saw his soft, tender side.

“I remember [Rabbi Ciment] fondly,” a student who attended NEHA in the 1970s wrote to the family. “[He] showed great love, [even as he was] very serious and strict in his ways … .” While Rabbi Ciment had a serious demeanor in school, there was another side as well, the student recalled. “He had a great laugh and would smile from ear to ear. I remember spending many Shabbatot in [the Ciment] house, especially in our senior year … He instilled much love in what he did and carried himself with great dignity.”

From Hungary to Lubavitch

Though he represented the name of Lubavitch for nearly three quarters of a century, Chaim Ciment’s roots stemmed from the vastly different world of prewar Hungary, where he was born in 1930 to Reb Yosef and Zissel Ciment in the town of Kisvárda (known as Kleinverdein in Yiddish). His mother passed away when he was about 5 years old. Chaim’s father brought him to America in 1938, where he and his second wife Frumet raised the boy in the Williamsburg neighborhood of Brooklyn, N.Y.

During the next few years, Reb Yosef Ciment and his brother Yaakov Yitzchok were instrumental in establishing the Sighet Chassidic court on the safety of American shores. There were no Hungarian yeshivahs at the time, and so, young Chaim was sent to study at Yeshivah Torah Vodaath in Brooklyn. But the intellectually curious teenager thirsted for more. Hearing that a Chabad-Lubavitch Chassid named Rabbi Yisroel Jacobson led an informal Chassidus class for students of Torah Vodaath, Ciment joined and began studying Tanya, the seminal work of Chabad Chassidic philosophy.

Along with many of his peers from this Tanya study group, Chaim started regularly attending farbrengens at 770 Eastern Parkway, where the older Chassidim would enthrall the youngsters with timeless Chassidic tales and teachings, infusing within them a rich appreciation for the Chabad Chassidic way of life.

Eventually, and with the blessings of his father, the gifted young student decided he wished to transfer to Tomchei Tmimim, the Lubavitcher yeshivah transplanted to New York by the Sixth Rebbe—Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, of righteous memory—upon his arrival from Europe in 1940. Then a dilemma arose: As a pillar of the fledgling Hungarian Chassidic community in America, Reb Yosef Ciment brought the Tzehilimer Rav, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Greenwald, from Williamsburg to Crown Heights, Brooklyn, for a private audience with the Sixth Rebbe. During this audience the Sixth Rebbe encouraged Rabbi Greenwald to open a Chassidic yeshivah in the Hungarian mold. The Tzehilimer Rav, who was especially impressed by the Sixth Rebbe’s insistence because his own yeshivah— Tomchei Temimim—was still in its earliest stages, acquiesced and opened the Tzehilimer Yeshivah, Arugas Habosem, in Williamsburg. Now with two Chassidic yeshivahs to choose from, Reb Yosef Ciment nevertheless chose to send Chaim to Lubavitch.

Reb Yosef was forever grateful that upon registering his son, the administration never asked him for tuition, only telling him he could pay whatever he could afford.

Chaim Ciment’s switch to the Lubavitcher yeshivah in the 1940s offered him a front-row seat to the early years of Chabad in America, and left him with a host of rare encounters and memories. For example, there was the time when, just as the sun was setting ushering in the holiday of Rosh Hashanah, Chaim rushed into 770 with his pan in hand. A pan, or “pidyan nefesh,” is a petition asking for the Rebbe to pray on one’s behalf, and it is the Chassidic custom to bring one to one’s Rebbe before Rosh Hashanah. This particular year Chaim was running late, and he dashed into the synagogue with the envelope including the note and also a dollar bill, hoping he could still have someone deliver it to the Sixth Rebbe.

Rushing up the stairs to the Sixth Rebbe’s room, he encountered the Rebbe’s son-in-law and later successor—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory. The Rebbe’s son-in-law, known as the Ramash at the time, asked the young student what he was after and took his note. Removing the money, the future Rebbe returned the bill telling Chaim he should keep it for himself, and that he would give the pan to the Sixth Rebbe.

Chuckling as he remembered the episode years later, he quipped: “I was the first Chassid to give the Rebbe a pan and the first Chassid to receive a dollar from the Rebbe!” (In the Chassidic tradition, only a Rebbe accepts notes with requests for blessings, thus Rabbi Ciment had handed the Rebbe a note several years before he accepted the mantle of Rebbe. In 1986, the Rebbe began distributing dollars for charity each Sunday to the many who would line up at 770 to receive a dollar and blessing.)

As a yeshivah student Rabbi Ciment was known for his vast Torah scholarship. As a diligent scholar, when he commuted from Williamsburg to Crown Heights by trolley or bus he always carried a Torah book with him. Among the books he took on those daily treks was Perashat Derachim, a deeply analytical, scholarly treatise authored in the early 18th century by Rabbi Yehudah Rozanes of Constantinople.

Arriving at yeshivah one morning in the late 1940s, Rabbi Ciment saw Rabbi Eliyahu Quint—at the time secretary of Merkos L’inyonei Chinuch, Chabad’s educational arm, and later a member of the Rebbe’s secretariat—searching the study hall at the Ramash’s request for a Perashat Derachim, the very book Rabbi Ciment had taken along with him. “I happen to have that book with me,” Rabbi Ciment spoke up, lending the book to the Ramash.

“A week goes by, two weeks, a couple of weeks; it’s not returned,” remembered Rabbi Ciment in an interview with Jewish Educational Media (JEM). Seeing the Ramash leading the prayers one day, he approached him after the service. “The book Perashat Derachim, do you no longer need it?” he asked the Ramash. “The Rebbe right away responds: ‘Regarding a Torah book, you never say ‘you don’t need it.’”

“I learned my lesson,” Rabbi Ciment reminisced. “It didn’t take long and the Rebbe did return the book; but I learned a very good lesson: Regarding a Torah book, you never say ‘you don’t need it.’ Who doesn’t need a Torah book? Of course you need it!”

In a private audience with the Rebbe held after he accepted leadership of the Chabad movement, the Rebbe turned to the young student and said: “They say that you have a good head.” The Rebbe then proceeded to guide him on what his focus in Torah learning should be, giving him a thorough regimen of advanced study.

Getting the Institution Back on Its Feet

In late 1953, Rabbi Ciment—along with several other students—were sent by the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, to assist with running the Boston Lubavitz Yeshivah—Achei Tmimim in Dorchester, Mass., which had been established 10 years earlier by the Sixth Rebbe.

In Boston, Rabbi Ciment was introduced to Esther Sonn, a native Bostonian. They married in 1956 outside 770 Eastern Parkway with the Rebbe officiating the wedding ceremony.

A short while afterwards, the young couple returned to Boston, and Rabbi Ciment was appointed dean of the school’s Judaics department.

The Lubavitz yeshiva, which eventually became known as NEHA, played a central role in developing the Boston Jewish landscape. When it was established with 12 students in 1944 there was only one other Jewish day school in town, and a Chassidic school was something unheard of. In its early years the yeshivah especially attracted the children of recent immigrants from Europe and of the Massachusetts rabbinate, many of whom wanted a more religious education for their children than was available elsewhere. It offered a stellar Jewish education in the Chassidic spirit, alongside a rigorous secular curriculum. It was also the first Jewish day school in the entire region to provide hot kosher lunches to all its students.

The school rapidly developed, eventually moving into the massive premises of the former Temple Mishkan Tefila in the adjacent neighborhood of Roxbury, where the school remained for a decade. The yeshivah’s reputation likewise grew, and among its board members were prominent Jewish Boston philanthropists including Samuel Bernstein, father of the conductor Leonard Bernstein—who performed at Lubavitz yeshivah dinners in the ‘60s and was honorary chairman of its scholarship fund—and E.M. Loew, of Loew’s Theater fame.

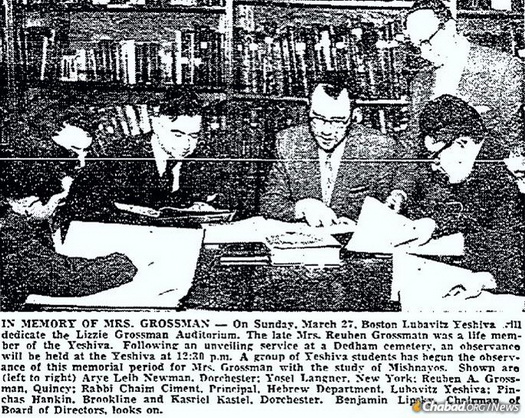

When Ciment arrived at the yeshivah its director was Rabbi Yehoshua Kastel. His son, Rabbi Kasriel Kastel, today the director of the Lubavitch Youth Organization in New York, recalls a young Chaim Ciment babysitting his older siblings on Shabbat afternoons. During his youth, until his family left Boston, Kastel was taught by Rabbi Ciment. Kastel fondly recalls Rabbi Ciment’s classes.

Years later, when Kastel would bump into Rabbi Ciment, the rabbi would always greet him warmly, retelling his favorite old stories yet again.

After the senior Rabbi Kastel suffered a heart attack in late 1967, he entrusted the leadership of the school entirely to Rabbi Ciment.

The period when Rabbi Ciment took school’s helm was a difficult one, for the Jews of Boston at large and the yeshivah in particular. During the previous decade the three old Jewish neighborhoods of Dorchester, Mattapan and Roxbury had slowly changed, but the mid-1960s saw their wholesale collapse.

“Unlike classic ‘redlining’ … the Boston experiment [in social engineering] provided a bizarre new twist,” write Hillel Levine and Lawrence Harmon in their book Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. “Under the guise of expanding homeownership opportunities for the city’s black community, the heads of twenty-two Boston savings banks were complicit in establishing a carefully limited and well-defined inner-city district within which, and only within which, blacks could obtain … attractive, federally insured housing loans.” The district lines they drew up completely skirted predominantly Irish and Italian white neighborhoods, as well as the leafy suburbs where the bankers themselves lived, leaving within its borders, “almost the entirety of Boston’s Jewish community … .”

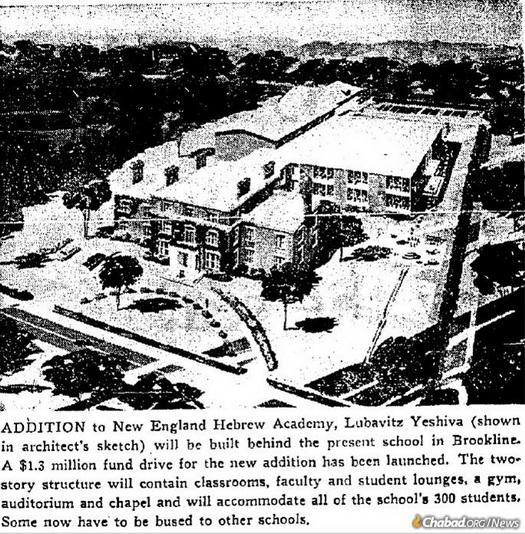

“Panic selling, blockbusting, street violence and rage”—including the devastating riots of 1967—quickly followed. The younger Kastel recalls black youths pelting the yeshivah’s school buses on their way to Roxbury, and by 1968 it was untenable for the yeshivah to remain on its campus any longer. That year NEHA purchased a massive campus in Brookline, one of the Boston neighborhoods where the city’s Jews had moved to, and soon began construction that yielded the modern addition that sits on the site today.

Along with the communal instability, when Rabbi Ciment was put in charge the school wasn’t in the best financial shape. A fundraiser par excellence, he worked to get the institution back on its feet—not only stabilizing the financial situation, but gaining financial security for decades to come.

Taking in the Wave of Russian Jews

With the mass emigration from the former Soviet Union of Jews in the late 1970s, immigrant children from Russia became a large part of the student body. Val (Zev) Busler was one such student. He arrived in Boston in 1979 with his mother and grandparents. A high-school age student at the time, they sent him to a public school in Boston’s Brighton neighborhood, where the immigrant boy did not fit in. Relatives introduced them to Rabbi Chaim and Esther Ciment, who took them in with minimal tuition—just several hundred dollars a year. From 1979 to 1982, Busler completed 10th, 11th and 12th grades at NEHA.

“We were assimilated Russian kids,” Busler tells Chabad.org. “All we knew is that we were Jewish—we could never forget that; it was stamped in our [Soviet] passport.” Rabbi Ciment ensured that Busler, along with other Russian-born boys, had a brit milah, something not easily done in the USSR, giving him his Hebrew name Zev. “We learned so much about what it means to be Jewish, we put on tefillin every day.” says Busler. “The secular education was also much better than the public school equivalent.”

Busler credits NEHA and Rabbi Ciment for his leading a proud Jewish life today, regularly attending Brighton’s Shaloh House for programs and services. “I married a Jewish woman, who comes from Kiev like me, and when we had our first child, I started getting more into religion, giving our two children a Jewish education, celebrating the holidays and learning Torah. Without Rabbi Ciment, I don’t think this would have happened.”

It wasn’t just him. “Thousands of other children had the same experience that I did,” vouches Busler, “almost all my former classmates, from non-observant homes, are religiously involved today, thanks to Rabbi Ciment’s foresight.”

‘Among the Towering Figures of Our Youth’

In the 1970s, Rabbi Ciment was struck with a debilitating and rare illness called Ankylosing Spondylitis, also known as Bechterew’s disease. This inflammatory condition, which has no known cure, can cause some of the spinal vertebrae to fuse over time, affecting the flexibility and posture of the body. “First, I felt pain in one joint, then another joint. Without exaggeration, all my joints I couldn’t move,” he recalled in an interview with JEM, “I even hurt when I coughed.”

Rabbi Ciment was hospitalized at the Massachusetts General hospital, where his doctor, who had suffered from the same illness and had limited movement, expressed his condolences for Rabbi Ciment’s sad and irreversible condition.

“Of course, we wrote to the Rebbe,” Rabbi Ciment recalled in the emotional interview. “The Rebbe’s answer was: ‘Es iz gornisht’— ‘It’s nothing.’”

And so it was.

“The remedy was aspirin—18 aspirins a day, which takes away the inflammation. And slowly I was able to move one joint, a second joint … And you see me now. The Rebbe said ‘It’s nothing.’”

Since Rabbi Ciment’s passing, his family and the yeshivah he cared so much for received an outpouring of condolences and well-wishes, with the many thousands he touched over the years recalling his impact on their lives.

“He was among the towering figures of our youth. An individual of remarkable humility who helped transform, indeed elevate, the state of Yiddishkeit for Boston Jewry,” wrote Jay Solomon. “His peerless dedication to the welfare of the yeshivah is a matter of incontestable record and deeply appreciated not only by those who lived through that era, but by all the generations that follow.”

“Failure was not an option,” says Busler. “Rabbi Ciment was a man of action and performed great things in his life, following what the Rebbe sent him to do. He was a template of what a shliach is all about to the highest level and he raised a beautiful family—and I am part of that extended family.”

In addition to his wife Esther, the rabbi is survived by their children: Zissie Nagel (Brooklyn, N.Y.); Goldie Gansbourg (Brooklyn, N.Y.); Rabbi Mendel Ciment (Brooklyn, N.Y.); Rabbi Dovber Ciment (Boston); Sarah Hecht (Brooklyn, N.Y.); Rabbi Pinchus Ciment (Little Rock, Ark.); Rabbi Sholom Ciment (Boynton Beach, Fla.); Rabbi Yaakov Ciment (Boston); as well as numerous grandchildren and great-grandchildren, many of whom serve as Chabad emissaries around the world.

This article has been reprinted with permission from chabad.org