Obituary: Rabbi Aharon Yaakov Schwei, 86, Beloved Rabbi of Crown Heights

by Motti Wilhelm – chabad.org

Rabbi Aharon Yaakov Schwei served in many positions throughout his life, including as a teacher, summer-camp rabbi and serving on the rabbinic court of the Crown Heights Jewish community in Brooklyn, N.Y. But throughout it all, say those who knew him well, he remained the same warm and unassuming Torah scholar that he was as a young man. When described by his students, family members or one of the thousands who approached him with halachic queries, a common denominator can be found in their stories and anecdotes: Rabbi Schwei was a man devoted to G‑d and His Torah, and dedicated to the spiritual and material welfare of his fellow Jew.

When he passed away on April 24 after contracting the coronavirus, community members said they felt orphaned. Though by that point hearts were already aching from the flood of tragic passings sweeping the community, this one was especially difficult. The community lost a leader, a guide and a mentor to countless. His funeral took place in the midst of the coronavirus lockdown. As the hearse wended its way through the neighborhood’s streets, young and old flocked to their windows and porches to pay their last respects to the rabbi who was known for his kindness.

“Rabbis and scholars are called the ‘eyes of the community’ and ‘heads of the thousands of Israel,’ ” the Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—wrote regarding the role and tremendous responsibility of a communal rabbi in his compilation Hayom Yom. “When the head is healthy, the body is then also healthy.”

Rabbi Schwei’s commitment to this vision was evident not just in his rulings on Jewish law, but in the gentle way he spoke with one and all, as well as the example he showed in leading a life dedicated to Torah.

The World that Was

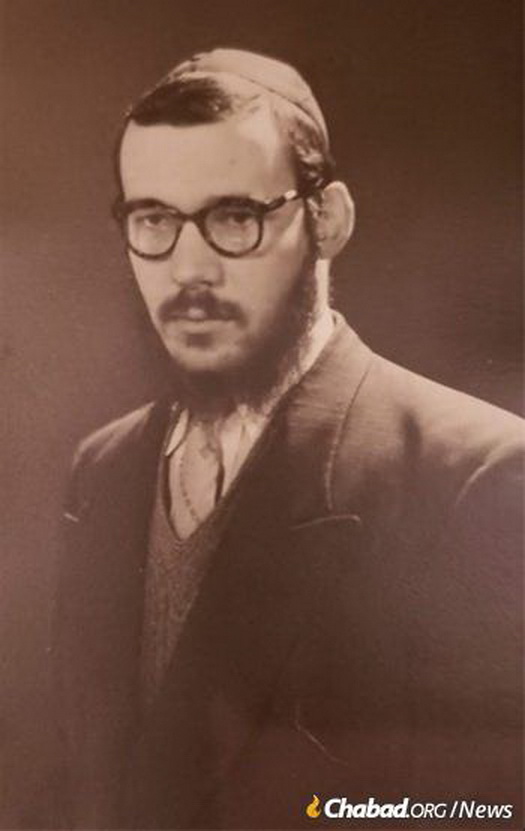

Aharon Yaakov Schwei was born to Rabbi Mordechai Eliyahu and Bunia Schwei on July 9, 1934, in the small city of Abo (Turku), Finland. His father, affectionately known as “Reb Mottele,” had studied in the original Tomchei Temimim in the village of Lubavitch before returning to his hometown of Dvinsk, Latvia, where he studied with the Rabbi Yosef Rosen, renowned as the Rogatchover Gaon. In 1930, the Sixth Rebbe—Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, of righteous memory—sent the brilliant young scholar to Abo to serve as the community’s rabbi and to teach its Jewish youth.

In 1935, a year after Aharon Yaakov’s birth, the family moved to Narva, Estonia, where Reb Mottele took up a rabbinic position and also served as the town’s ritual slaughterer, providing kosher meat for the community. The coming few years were pleasant ones for the family, a time of both material and spiritual bliss. Their father had a respectable position, the family was well provided for, and guests were a frequent sight at the Schwei table. Decades later, Rabbi Schwei would fondly recount to his grandchildren memories from those early years, such as going with his father to supervise the milking of cows on a farm to provide kosher milk for the family. He especially recalled their family’s joy when the postal service delivered a new Chassidic discourse that had just recently been taught by their beloved Rebbe, by that time living in Poland. The family would dress in Shabbat clothes and Rabbi Schwei, too young to study the discourse with his father and brothers, would long remember his youthful yearning to join them.

All this came to an abrupt halt in 1939 with the outbreak of World War II. While the Baltic states had been independent countries in the inter-war years, the secret protocols of the Hitler-Stalin Non-Aggression Pact designated them as in the Soviet’s sphere of influence. In June of 1940, beginning with Estonia, the Soviets invaded the Baltics, annexing them later that summer. As was the case across Soviet territories, food quickly became scarce, and the new government began dictating every aspect of life. Although small, Estonia’s Jewish community had until this point been free to worship as they pleased, this brief era ending when the Soviets introduced their Communist persecution of religion.

Then things went from bad to worse. In June of 1941, Hitler invaded the Soviet Union, and the Nazis began bombing Estonia mercilessly. Finding enough food to survive became a challenge. Men and women were forced into hard labor, digging trenches to stop Nazi tanks. Despite the dangers, Bunia Schwei refused to allow her husband to dig trenches, insisting she would go in his stead. “If something happens to you,” Rabbi Schwei would remember his mother arguing to his father, “who will teach our children Torah?”

Not only did she work, she overfulfilled her quota to the extent that the foreman allowed her to leave early. On the day the Schwei family fled Estonia, she finished her work digging while her family waited, and then they caught one of the last trains out of the city.

Years of Sorrow

Escaping from Estonia, the Schwei family headed deeper into Russia towards the Ural Mountains. The train ride was fraught with danger; every few miles, the passengers had to disembark and cover themselves with camouflaged cloths to hide from Nazi planes flying overhead on bombing missions and strafing the roads. Rabbi Schwei would later recall the planes flying so low he was able to make out the faces of the German pilots and then lying under blankets whispering Psalms together with his father.

Arriving in a tiny village in the Sverdlovsk region, the family was finally safe from the war. Living conditions, on the other hand, remained severe. The freezing cold, the lack of any food besides potatoes and unbearable living quarters kept the family moving on, eventually making their way to the small town of Vobkent, Soviet Uzbekistan.

In the winter of 1942, just as they tried to settle down, tragedy struck. While crossing a makeshift bridge made up of felled trees, Rabbi Mordechai Schwei slipped into the water. By the time he managed to drag himself out of the river, a large amount of water had filled his lungs and he collapsed on his arrival home. Reb Mottele was rushed to the local hospital, where he could not be revived, tragically passing away at the age of 38.

The hospital ignored the desperate cries of the young new widow and threw Reb Mottele’s body in a communal grave with the other deceased, denying him even of the dignity of a Jewish burial.

Only a short while later, young Aharon Yaakov’s 14-year-old sister, Hinda, contracted an infection. With no antibiotics available, she passed away shortly afterward. But Bunia Schwei was determined to give her daughter the Jewish burial her husband had been refused. Taking her daughter’s body in her arms, Bunia, together with her three sons, carried her into a forest and buried her with her own hands. Heading back home, she held her young sons’ hands. In a display of pure faith that was burned into Aharon Yaakov’s mind until the end of his life, his mother turned upward to G‑d and instead of bitterly complaining, sang a heartfelt song thanking Him for helping bring her daughter to Jewish burial. “A dank dir Ribbono Shel Olam vos Du host mir geholfen,” she sang in Yiddish. “Boruch Hashem iz gekuman tzu kever Yisrael.”

Continuing along their long road of tribulations, the family spent the next few years in one city after the next. All the while, Bunia made sure her sons learned Torah whenever possible. While living in the city of Bukhara, she encountered Rabbi Dov Berish Weidenfeld, the world-renowned “Tshebiner Rov,” and persuaded him to teach Torah to her eldest son. Working endless hours scrubbing floors and washing people’s laundry in the frozen river, Bunia pooled every kopek with the goal of sending her sons to learn in the underground Chabad yeshivah in Samarkand.

When she had enough money to send her oldest son, Boruch Sholom, she purchased a ticket and begged a Lubavitcher Chassid in Bukhara heading to Samarkand to take her son with him. Afraid, the Chassid, R’ Leizer Mishulovin, refused. Bunia, determined that her children would study Torah no matter what, followed Mishulovin to the station and surreptitiously placed Boruch Sholom on the same car, telling her son that if authorities asked who he was with to reply he was a runaway. A short time later she had saved enough to send her second son, Aizik. This time Mishulovin, back in Bukhara and having seen Bunia’s dedication, agreed to take him along. By the time it was Aharon Yaakov’s turn, her youngest, the little boy cried he didn’t want to go because he was afraid he’d never see her again. But Bunia promised him that she’d soon have enough money to join him.

This time there wasn’t even enough money to buy Aharon Yaakov a ticket. Instead, Mishulovin, once again traveling from Bukhara back to Samarkand, hid the boy among the luggage. Bunia would be forever grateful to Mishulovin for having risked his own life to enable her children to study Torah.

In Samarkand, Aharon Yaakov and his brothers learned under venerable Chassidim, including Reb Nissan Nemenov, Reb Berke Chein and Reb Elya Chaim Roitblat, while they waited for their mother.

Eleven months later, Bunia had earned enough money for her own train ticket. Arriving by train in hunger-ridden Samarkand with her one beaten suitcase, she was greeted by a scene of the sick, dying and dead lying throughout the station. Amidst the silence of death she was surprised to suddenly hear a familiar voice whisper “Mama!” The entire station turned to witness 9-year-old Aharon Yaakov running towards his mother for an emotional reunion.

Later, when she asked her son how he knew she was coming that day, Aharon Yaakov explained that he hadn’t. Holding on to his mother’s parting words, every time he heard there were trains arriving from her location, he’d walk the few kilometers to the station in his tattered shoes and wait. He didn’t know when she would get there, but he never gave up hope that she would.

The New World

In 1946, the family traveled to Moscow and from there to Lvov, where they joined about 1,000 Chabad Chassidim and crossed the border out of the Soviet Union using forged Polish passports. From there they made it across to Prague and then on to the displaced persons camp in Pocking, Germany. In the camp were many Chassidic figures, and Aharon Yaakov spent his formative yeshivah years there, learning from them, and then at the new Lubavitcher yeshivah that opened in Brunoy, a suburb of Paris.

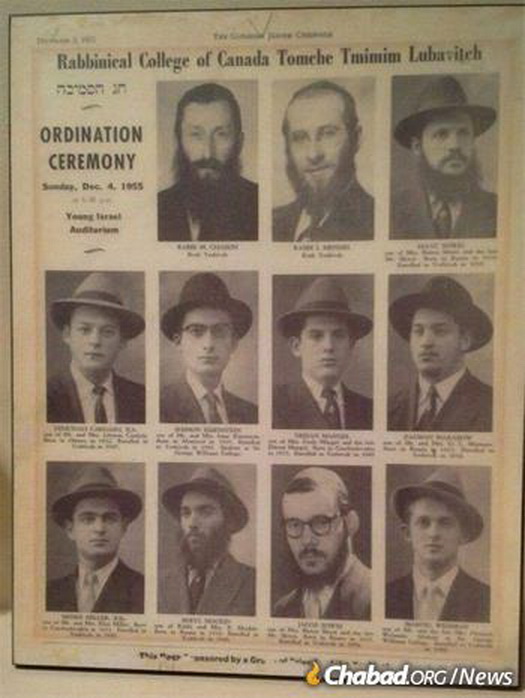

In 1951, the Schwei family moved to Montreal, Canada. There, with life back to a semblance of normalcy, Aharon Yaakov spent many months studying with his older brother Aizik and with other students. Having long before acquired a name as a serious student and budding Torah scholar, Aharon Yaakov was part of the first group from the Montreal yeshivah to receive rabbinic ordination.

Rabbi Schwei first met the Rebbe on a visit from Montreal in 1952. He then had his first of many private audiences where he merited to receive unique and rare instructions. In one audience, the Rebbe personally advised him to begin praying at length and with deep concentration—a concept taught in Chassidic works and observed by many of the Chassidic greats Rabbi Schwei had witnessed during his early years. When he commented that it would be difficult for him to pray for hours on end every single Shabbat, the Rebbe suggested that he take a break after the Shacharit prayer to allow himself to afterward pray Mussaf with the same fervor. In 1955 Rabbi Schwei received rabbinical ordination in Montreal, and over the coming years, the Rebbe would continue to pay close attention to him, including suggesting specific halachic works for him to study.

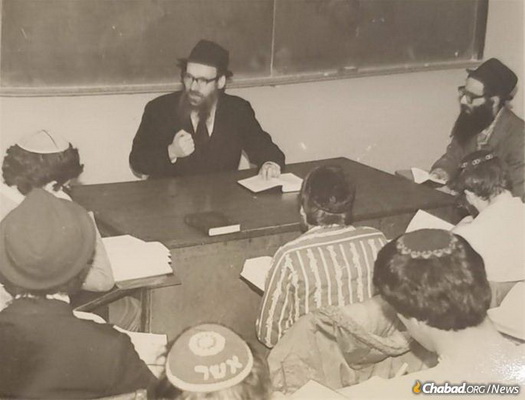

In Montreal, Rabbi Schwei began his decades-long career in education, while at the same time continuing his own studies. Gaining fame as a Torah scholar, he was later chosen to edit Torah works, among them those of his brother Rabbi Aizik, a formidable Torah scholar in his own right.

Moving Close to the Rebbe

In 1961, Rabbi Schwei moved to Crown Heights to be in close proximity to the Rebbe. That same year, he was introduced to Rachel Calvary; they married a few months later. After his marriage, he was offered a position at the Lubavitch Yeshiva on Bedford Avenue, the perfect fit for a man both with a love for Torah and a sensitivity to connect to every student.

Two years later, he wrote a letter to the Rebbe requesting that he be appointed as the Rebbe’s emissary and sent to a distant location. The Rebbe responded by writing that his shlichut would be to continue teaching in the yeshivah and bestowed a warm blessing for success in education.

Students recall Rabbi Schwei’s kindness to each one of them. He strove to educate them to love the Almighty, and to appreciate the wealth and the richness of Torah study. At the same time, the care he showed for each student was not dependent on the student’s grade or academic level. One pupil recalled how, when he was caught doodling during a class, Rabbi Schwei did not reprimand him. Instead, himself a talented artist who enjoyed drawing, Rabbi Schwei showed him how to use a pencil to shade the picture better.

During his years of teaching, Rabbi Schwei also served in a semi-rabbinic capacity. During the summer months, when students were on summer vacation, Rabbi Schwei would spend his break in Camp Gan Yisroel of Montreal, acting as the camp rabbi. Although not a community position, complicated halachic questions can arise in a summer camp, such as questions of kosher or an eruv, and Rabbi Schwei was well qualified to answer those queries.

In 2000, Rabbi Yehuda Kalmen Marlow, one of the three rabbis on the Crown Heights rabbinic court, and a senior rabbi in the community, passed away, leaving a huge gap. Almost immediately, the community began searching for someone to fill the position. Although initially hesitant to leave his position in education, Rabbi Schwei eventually agreed to run as a candidate, realizing that as rabbi of a community, he will not be stopping his role as an educator, but rather broadening it. In 2003, elections were held, and Rabbi Schwei was elected by a vast majority of the community.

Over the next 17 years, as rabbi of one of the largest Jewish communities in the United States, Rabbi Schwei continued to act in the same unassuming manner, always with a warm smile for anyone he encountered. Bound by halachah, a rabbi is not always able to make a decision that will make a petitioner happy. But no matter the circumstance, Rabbi Schwei would always leave off with a caring word, encouraging them to trust in G‑d that all would be well.

“My father was a living example of one who serves G‑d with every fiber of his being,” said his daughter, Dinie Rappaport, herself a longtime educator. “To do so involves mindful and intentional decisions minute by minute, even every moment, that you want to dedicate your life to a higher purpose. These choices become our story, and his choices became the story of his life.”

During the last few months of his life, Rabbi Schwei suffered from poor health, yet continued to pray with his trademark passion and answer halachic questions whenever able. As the coronavirus struck the Crown Heights community, Rabbi Schwei contracted the illness. Thousands of his students and community members prayed for him as he lay in the hospital. On the 30th day of the Hebrew month of Nissan, he passed away, leaving a void in the hearts of his family, his thousands of students and the Crown Heights community.

From his hospital bed during his last days, Rabbi Schwei took part in a joyous family celebration via Zoom, asking those present to say a l’chaim on his behalf. Considering his predicament in the hospital, his last words were “Gam zu le’Tovah,” or, “This too is for the best.”

In addition to his wife, he is survived by their children: Rikvah Schwei (Israel); Rabbi Yosef Yitzchok Schwei (Luton, England); Chana Eta Turk (Cordova, Argentina); Rabbi Mordechai Eliyahu Schwei (Brooklyn, N.Y.); Nechama Dina Rappaport (Brooklyn, N.Y.); Shterna Sara Ginsberg (Brooklyn, N.Y.); Devorah Schwei (Baumgarten) (Brooklyn, N.Y.); Rabbi Boruch Sholom Schwei (Brooklyn, N.Y.); as well as many grandchildren and great-grandchildren.