Obituary: Soviet Jewry Activist Gedalya Korf, 90, ‘Said Little, Did Much’

by Dovid Margolin – chabad.org

He was the bane of journalists and interviewers, a tight-lipped, Soviet-born Lubavitcher Chassid whose poker face belied the horrors he had seen and the secret work he spent decades immersed in. As one of the founders and leaders of Lishkas Ezras Achim, a Chabad organization that quietly sent massive amounts of material and spiritual aid to Jews behind the Iron Curtain over a period of three decades, Rabbi Gedalya Korf earned a reputation as a man who “said little [but] did much.”

Korf passed away from COVID-19-related complications on March 30 (5 Nissan), at the age of 90, having kept most of his life’s work classified until the very end.

Korf’s activism on behalf of Soviet Jewry began in 1964. At the time, there was no American Soviet Jewry movement, no lapel pins and no slogans, no protests nor protesters. All there was were 3 million Jews living thousands of miles away under a Communist regime that tried its utmost to cut them off from their roots, and enslave them in body, mind and soul. That year, the Soviet regime released the venerable Chabad Chassid Reb Mendel Futerfas, who had spent nine years in the Gulags; Futerfas went first to London, where he reunited with family after nearly 20 years, and then on to the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn, N.Y., to see the Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—for the first time in his life.

There, Futerfas organized a meeting at the modest home of the late Rabbi Moshe Levertov. He explained to the group—Chabad Chassidim who had themselves escaped Stalin’s USSR after the war—the dire circumstances of their brethren back in Russia and admonished them for living in what by Soviet standards was luxury while Jews in Russia were starving. Futerfas suggested that they begin sending care packages to the Soviet Union, the items to be either used or, better yet, sold on the black market. Right then and there, the men—Levertov; Gedalya Korf; Reb Leibel Mochkin; Reb Moshe Morosow; and Rabbi Zalman Shimon Dworkin (the rabbi of the Lubavitch and Crown Heights communities)—founded Lishkas Ezras Achim, which translates as “Aid to Our Brothers.”

This was not the first nor only Chabad effort on behalf of Soviet Jews. The Rebbe had long directed a network of aid for the Jews of the Soviet Union, meeting and corresponding on the topic with a wide range of Israeli officials, American Jewish communal leaders and others, and always remaining in surreptitious contact with Russian Jewry. In order to never risk the lives or livelihood of any Soviet Jews, this activism was always kept utterly secret. Ezras Achim, the new grassroots effort, could be no different.

“Russia was still a very dangerous place and there was a great need for secrecy,” Korf recalled in a recent—and rare—interview with A Chassidishe Derher magazine. “Specifically, the Rebbe’s involvement needed to stay secret. Therefore, Ezras Achim was never directly or officially associated with the Rebbe. [T]he Rebbe’s constant emphasis was on the importance of secrecy.”

Korf and the others, whose wives all took part in the work, would spend time gathering information about the Russian black market to find out which items would get the best price on the street. Sometimes, this could mean Parker pens or colorful bed sheets. Later, it became American jeans. Ezras Achim would also scour the American Jewish address books to match listed Jewish last names with similar-sounding ones in the Soviet Union, so that return addresses on packages entering the Soviet Union bore a name similar to the one in Russia—this way giving the appearance that it was being sent by family and not raise suspicion of an organized effort. The Soviet government levied a 100 percent tax on all packages, and so whatever the items cost Ezras Achim had to pay double to get it through.

At the same time, anything needed for Jewish life, from prayer books to the Five Books of Moses, from tefillin to mezuzot, needed to be smuggled in as well. In an interview with Chabad.org, Levertov’s wife, Bracha, recalled scraping eyeliner out of makeup kits to replace it with black ink suitable for a scribe to use in the writing or fixing of a Torah scroll, tefillin or mezuzot.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Ezras Achim began sending American Jews into the Soviet Union posing as tourists, sending with them whatever was needed on the other side. While many of these messengers were Chabad Chassidim—rabbinical students, rabbis or couples—these volunteers came from a broad spectrum of American Jews.

“The parameters of my third trip [to the Soviet Union] were clearly supply and inspiration,” recalled Ron Rubin, a veteran professor of political science at the Manhattan Community College, City University of New York, in 2013. “Sponsored by the Chabad Lubavitch organization Lishkas Ezras Achim, two young rabbis and I spent two weeks there. We brought few personal effects, but at a warehouse in Brooklyn’s Crown Heights our suitcases were stuffed with Jewish books and sundry ritual items ranging from shechitah [kosher slaughter] knives, kosher yeast and burial shrouds. On the plane, we spoke seriously of the possibility that our goods would be confiscated at Soviet customs and that we could be either thrown out of the country or arrested. On that trip, I saw one of the young rabbis secretly circumcise an adult male who was lying on a simple table.”

Ezras Achim’s Brooklyn basement warehouse where Lubavitchers filled false-bottomed suitcases with, among other things, tefillin and Nikon cameras, would become the stuff of legend.

The organization’s motto, spelled out on its stationary, was a quote from the Fifth Rebbe—Rabbi Shalom Dovber of Lubavitch—written in Hebrew and English: “One action is better than a thousand sighs.” Once, when Ezras Achim’s committee, which would expand over the years, wrote a report to the Rebbe where they outlined the many things that had recently gone wrong, the Rebbe responded by merely circling the quote on the letterhead and drawing an arrow to their words of disappointment.

In all of this, Gedalya Korf was one of the leaders. When in the early 1970s the Soviet government demanded $70,000 for the release of Dr. Herman (Yirmiyahu) Branover—the money, the Communists claimed, was to pay for the advanced education “the people” had given the Jewish scientist—Korf raised the money. Later, in the early 1980s, he left his knitwear business and began working at Ezras Achim full time. Despite the great responsibility, including the vast financial burden of supporting the operation, Korf always shunned attention.

“The work was always the most important thing for him,” recalled his younger brother, Rabbi Avraham Korf, the founding director of Chabad of Florida. “Work, not talking.”

Black Years

Gedalya Korf was born on Dec. 29, 1929 (25 Kislev, 5690), in Kharkov, Soviet Ukraine, the eldest of Rabbi Yehoshua (Shea) and Chaya Rivkah Korf’s seven children. The Korfs both came from deeply rooted Lubavitcher families, and R’ Shea had directed the Kharkov branch of Chabad’s underground Yeshivat Tomchei Temimim until it was discovered and shut by the government in 1929.

Those were bitter years in the Soviet Union, both materially and spiritually. At the time of Gedalya’s birth, Stalin had recently begun implementing the Marxist agenda of forced collectivization, which in the early 1930s led to mass famine in Ukraine and other parts of the Soviet Union. The 1920s had seen a massive Soviet campaign of religious persecution, leading to closure and confiscation of synagogues, Jewish schools and other communal properties and organizations, and this would only intensify in the 1930s.

Despite the dangers, the Korfs were willing to risk everything to give their children, starting with their firstborn, an authentic Jewish education. But according to Soviet law they were required to enroll Gedalya at a state school. Fearing that neighbors would report them for not sending their son to school, at the age of 8 or 9, Gedalya was sent to live with his maternal grandparents in the town of Krolevets, about six hours away, where he could quietly study Torah with his grandfather.

“Kharkov was a big city, there were a lot of eyes,” said Korf’s son, Rabbi Sholom Ber Korf, director of Chabad of Delray Beach, Fla. Yet life was still dire. “He remembered six months during which the only thing they had to eat was cabbage.”

Korf’s father was a religious, bearded Chabad Chassid and that, combined with the general overwhelming atmosphere of terror directed by Stalin, meant his life was in constant danger. “Our father was always on the run, always in hiding,” recalled Rabbi Avraham Korf. “Gedalya, who was three years older than me, became very much a leader.”

After Hitler invaded the Soviet Union in 1941 and began his deadly thrust into Ukraine, the Korf family fled Kharkov under falling bombs and headed east, eventually making their way to Samarkand, Soviet Uzbekistan, where a refugee Chassidic community formed alongside the indigenous Bukharian Jewish one. While to a limited extent safe from religious persecution, the war-time starvation and malnourishment took its toll on the community, with nearly each family losing a loved one—the Korfs lost two children before they left Samarkand—to a horrible death.

When the war was over, the USSR offered repatriation to Polish citizens who had entered its territory. In 1946, a large number of Chabad Chassidim availed themselves of this opportunity to escape their hell. Family by family, those who made the decision to try to break for it headed to Lvov, Ukraine, where they could purchase false or forged Polish documentation and board a train to the West. Gedalya pushed his parents to join those escaping. Rabbi Avraham Korf recalled Gedalya assisting their parents with another one of their brothers, who was ill at the time.

“He carried our brother from Samarkand to Lvov,” said Korf, some 2,000 miles. “Then in Lvov, our brother passed away anyway.”

Forged papers and purchased tickets in hand, Gedalya was entrusted with selling the last of the family’s effects in Lvov.

“He almost missed the train,” remembered his brother. “We were all waiting, and he got on at the last minute.”

Land of Opportunity

The Korfs went first to a displaced persons camp in Pocking, Germany, then on to Paris. In 1950, a 20-year-old Gedalya Korf arrived in the United States to study in the Lubavitcher yeshivah in Crown Heights, this time in the open. Not long after arriving he, together with a few other recently arrived yeshivah students, had a private audience with the Sixth Rebbe—Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, of righteous memory. The Sixth Rebbe passed away less than a week later.

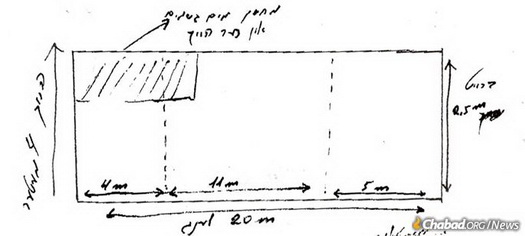

Settled in New York, Korf set things up in America so that his parents and family could join him in 1953. A year later, his father was searching for a business to enter when, nudged in the direction by the Rebbe, he came upon the idea of opening a shmurah matzah bakery. Gedalya had previously worked in the other shmurah matzah bakeries—there were only two in the United States at the time—where he had instituted process innovations to make things run smoother. When the elder Korf’s Lubavitch Matzah Bakery opened on Manhattan’s Lower East Side in 1954, Gedalya’s innovations—setting the bakery up with distinct zones, building seperate rooms for flour and water—came with him. Today, his innovations are industry standards.

“I was more than involved” in setting up the matzah bakery, Korf recounted in a hard-fought interview with Chabad.org. Despite Korf’s reticence in granting the interview, once he began discussing the bakery’s engineering details, a slight smile appeared on his face and he didn’t stop.

Korf married American-born Fradel Nesha Bracha Winter in 1955, and they settled near the Rebbe in Crown Heights. To support his growing family, Korf utilized his engineering mind to become a mechanic at a knitting factory. He eventually became a foreman and then opened his own knitwear factory together with a partner, starting out in Manhattan’s Garment District before moving the operation to a 100,000 square-foot facility in Jersey City, N.J.

“He was very bright, he would invent his own specialized machines and then have engineers build them for him,” recalled his daughter, Sarah Kessler. One attached pom-poms onto knit hats, another affixed fringes to sweaters, all of them were his own design.

“But Ezras Achim was always his passion,” she added. “Even before he started doing it full time, that’s what he was fully involved in.”

Soviet Jewish Renaissance

Over the years, Ezras Achim’s work continued to expand.

“Besides for the regular pairs of emissaries and occasional couples, we periodically sent individuals who specialized in a certain field,” Korf told the Derher. “We once sent … Dr. Kenneth Prager [today, professor of clinical medicine, and director of clinical ethics and chairman of the Medical Ethics Committee at Columbia University Medical Center] to go deal with the state of medicine in the Jewish community in Russia.”

Even when it was other Jewish organizations funding the trip to the Soviet Union, it was Ezras Achim to which the volunteer travelers turned when they needed addresses and materials to bring along with them.

“Luckily, we were placed in contact with the Ezras Achim organization of Lubavitch in Brooklyn and they provided us with the following items,” reads a 1984 trip report in Ezras Achim’s archives written by a pair of American Jews who went on behalf of another American Jewish organization. “2 pairs of tefillin; 2 taleisim; 2 Nikon Cameras with accessories; 12 cans of meat; 18 packages of Cholov Yisrael cheese; 2 large boxes of shmurah matzah; and ointment medicine for [redacted]’s baby, and offered an array of electronic appliances as well. And they delivered the items to our house one day after speaking to them.”

Ezras Achim also built the country’s first new mikvahs.

With Chabad’s own historic roots firmly planted in the Soviet Jewish story and the Rebbe’s decades-long quiet battle to keep Judaism there alive, when the Soviet Union began coming apart, it was only natural that permanent emissary couples be sent there. In 1990, under the aegis of Ezras Achim, Rabbi Berel and Chanie Lazar were sent to Moscow, Rabbi Moshe and Miriam Moskovitz to Kharkov, and Rabbi Shmuel and Chanie Kaminezki to Dnepropetrovsk. Today, there are more than 150 Chabad emissary couples serving the Jewish community of the former Soviet Union.

Korf, who remained sharp until the end of his life, rarely spoke about any such details. When Chabad.org approached him a few years ago to ask about a particularly sensitive 1986 operation to move a Jewish body from a cemetery under threat of demolition by Soviet authorities, in which Ezras Achim was involved, he looked into the distance and said he couldn’t recall any details. A few moments later, when the name of a religious Soviet Jew whom Korf had known well during the same era came up in conversation, his demeanor changed and a warm smile crossed his face.

“How is he doing?” he asked, with genuine interest. “Please send him my warmest regards when you speak to him next.”

But it wasn’t only his Soviet Jewry work that he kept quiet. Kessler, his daughter, said that the head of a North Americanyeshivah recently told the Korf family that when his yeshivah initially opened he received seed money from an organization. Later, he found out that all that funding had come from Gedalya Korf.

“My father wasn’t a talkative person; he never tooted his own horn,” said Kessler. “But if someone was suffering, he’d send them an envelope—always something to help someone else, always in a quiet way.”

Korf was predeceased by his wife. He is survived by their children: Rabbi Yossi Korf (Brooklyn, N.Y.); Rabbi Yanky Korf (Brooklyn, N.Y.); Sarah Kessler (Montreal); Rabbi Sholom Ber Korf (Delray Beach, Fla.); Dini Ciment (Boynton Beach, Fla.); Rabbi Alter Korf (St. Petersburg, Fla.); and many grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

He is also survived by his siblings, Rabbi Pinchas Korf of Brooklyn, N.Y.; Rabbi Avraham Korf of Miami, Fla.; and Batsheva Shemtov, Oak Park, Mich.

Readers are asked to say tehillimfor Rabbi Korf’s son, Yaakov Aharon ben Fradel Nesha Brocha, who is currently battling COVID-19.

With special thanks to “A Chassidishe Derher” magazine.