Sonia Kaplan, 98, Stood Up to Stalinist Persecution and Raised Chassidic Family

by Menachem Posner – chabad.org

Sonia (Sarah Pesha) Kaplan, who stood up to Stalinist persecution and survived a Polish pogrom to raise a Chassidic family after emigrating to England and then America, passed away Monday. She was 98 years old.

She was born in rural southwestern Russia in 1921 as the fledgling Communist regime was tightening its iron grip on Russia’s Jews. Her father, Rabbi Nochem Pinson, was a devoted Chabad Chassid who lived and breathed Torah study and mitzvah observance. Her mother, Chera, was the daughter of Chaim Chaikel Schapiro, a wealthy Chassid in the town of Starodub.

Living near her maternal grandparents, young Sonia Pinson lacked nothing in those first years. Like her father, her brothers were students in the Chabad yeshivah system, which by then had gone underground since propagating religious belief among youth was illegal.

By the time she reached adolescence, however, her grandfather’s businesses had been confiscated, and the family was destitute.

Desperate, the family moved to a kolkhoz, a farming collective. However, Nochem’s staunch devotion to Shabbat meant that the family was not allowed to benefit from the farm’s produce, and they found themselves starving.

From there, they moved to Kharkov, which was then home to a thriving secret Chabad community. Sonia attended public school but was always careful never to break Shabbat. Naturally bright, she helped other students with their work in exchange for small favors that would help her cover her repeated absences and refusal to write on Saturdays and Jewish holidays.

The Pinson home was often the site of spirited farbrengens, Chassidic gatherings where words of inspiration and soulful singing would transport participants to a better time when Jews need not hide their fealty to Judaism.

But disaster struck. In 1939, many of the leaders of the Chassidic underground, including Nochem Pinson, were arrested for their counterrevolutionary activities. Chief among Nochem’s crimes were the farbrengens he hosted.

Recently translated documents from the copious files kept by the secret police reveal that throughout the months of his arrest and torture, Nochem Pinson remained tight-lipped, refusing to divulge information that would implicate anyone.

When Sonia, by then a 10th-grade student, was taken in for questioning, she too didn’t give any information away.

Even though she completed her schooling as a chemical engineer, she never received her diploma because she would not renounce her father and his “antisocial” ways.

Nochem was sentenced to five years of forced labor in Siberia, from which he never returned. The family relocated to Samarkand, far from advancing Nazi troops and prying Communist eyes.

Making Their Way From Europe to America

In Samarkand, in 1944, Sonia was introduced to a young scholar by the name of Moshe Binyomin Kaplan. Like her, he was an orphan, as his father had also been taken by the Communists for the crime of upholding Judaism. The two married in 1945, determined to rebuild all that Stalin and his minions were determined to destroy.

After the war’s end, Moshe Binyomin obtained false identity papers, presenting the couple as Polish refugees who were allowed to leave Russia.

Sonia went into labor with her eldest son, Nochem, named for her father, while still in Russia. In the hospital, she could not remember her assumed name or date of birth, and pretended to be mute the entire time rather than risk revealing her true identity.

As they traveled from Lviv (then Russa) to Łódź, a doctor told her that her infant needed more air and was in danger if he were to remain in the cramped railroad car. She crossed the border to freedom between two careering train cars clutching her gasping baby, while her husband held onto her to prevent her from falling off the train.

Upon arriving in Poland, they spent the night in the remains of the Łódź ghetto, during which she had her sister-in-law clutch their infant boys, both named Nochem, while their husbands held shut the rickety door, which drunken Poles tried to force open. Even though the Germans had been defeated, the atrocities of the Holocaust had yet to subside.

Living in the Poking DP camp in Germany and then among fellow refugees in France, the Kaplans welcomed their next son, Leibel, named for his paternal grandfather, Rabbi Aryeh Leib Kaplan. In the DP camp, the families lived in large halls, with sheets providing a modicum of privacy. They bunked “next door” to Rebbetzin Chana Schneerson, mother of the Rebbe, who shared parenting advice, and developed a lifelong friendship Sonia and her children.

During this time, Moshe Binyomin completed his rabbinic ordination and soon attracted the attention of Rabbi Yechezkel Abramsky, chief of the London Rabbinical Court. Impressed by the young Chassidic scholar, Abramsky invited the couple to settle in England, where Moshe Binyomin engaged in shechitah, teaching and the rabbinate.

In the mid-1950s, the Kaplans and their family, which by then included another son, Shmuel, and a daughter, Cherry, made their way to New York, settling in Brooklyn.

Well-educated and technically inclined, Sonia was involved in her husband’s sweater factory. Aristocratic by nature, she maintained her European good taste and comportment.

She watched with pride as her children and grandchildren fanned out across the globe to serve as Chabad-Lubavitch emissaries, carrying on the work for which their grandfathers had given their lives.

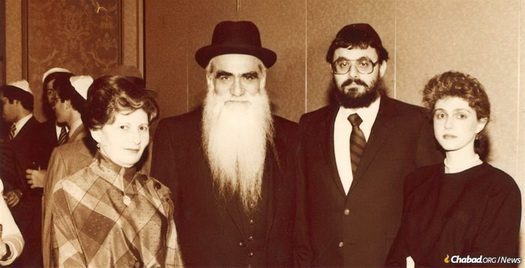

Predeceased by her son Rabbi Aryeh Leib Kaplan in 1998, and her husband in 2005, she is survived by Rabbi Nochem Kaplan (Brooklyn, N.Y.); Rabbi Shmuel Kaplan (Baltimore); and Cherry Ulman (Hashmonaim, Israel); as well as grandchildren, great-grandchildren and great-great-grandchildren.