What It’s Like to Be Jewish in Estonia

In 1941, the Nazis declared Estonia, a small nation on the Baltic sea, “Judenfrei” (“free of Jews”). Indeed, fewer than a dozen Jews are known to have survived the Holocaust in Estonia. The Nazi slaughter was followed by decades of Soviet repression of religion. Yet the Estonian Jewish community is undergoing a Jewish renaissance few could have ever imagined. Torah classes, kosher food, a daily “minyan” and other signs of a vital Jewish life continue to crop up in Tallinn, the capital city of Estonia.

Eliyahu (Ilja) Šmorgun, Ph.D., a 32-year-old native of Tallinn who lectures on human-computer interaction at Tallinn University and is a leader of the local Jewish community, offers details on this demographic turn of events.

Q: Can you share some basics about your country and its Jewish history for readers, most of whom have probably never set foot in Estonia?

A: Estonia borders Russia, and was part of Czarist Russia from 1710 until the collapse of the empire in 1917, which led to the Estonian War of Independence that ended in 1920. An independent nation existed here until World War II, and by the end of the war, Estonia was firmly under the thumb of the USSR. In 1990, Estonia declared its independence. It is now a democratic member of the European Union with a well-developed educational and economic program in place.

The first Jews to settle here we the “Cantonists,” Jewish boys who had been forced into the Russian army for 25-year terms of service. After that ordeal, they and their children were granted the privilege of settling in parts of the Russian empire normally forbidden to Jews, including Estonia.

Historically, life for Jews here was good, and Jewish people enjoyed freedoms here beyond those of their neighbors in Russia, for example. Before the outbreak of the Second World War, there were several synagogues in a number of Estonian cities, and Jewish life was quite rich.

The Soviets invaded Estonia in 1940 and deported approximately 10 percent of its estimated 5,000 Jews to prison camps in Russia. As the Germans advanced into Estonia in 1941, most Estonian Jews escaped to Russia, where many managed to survive. Virtually all who remained, estimated to be nearly 1,000 people, were killed by the Nazis and local collaborators.

During the Soviet period, many Jews came to Estonia from other parts of the Soviet Union, such as Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova, etc.

This is why, although 70 percent of the local population speaks Estonian, Jews are almost all among the 30 percent who speak Russian at home.

Q: What was it like to grow up Jewish in Estonia?

A: Most people of my generation grew up knowing virtually nothing about Judaism. The great Choral Synagogue of Tallinn had been bombed during the war, and no one thought of rebuilding it.

My great-grandparents and their generation had stopped observing Judaism in the early years of the Soviet Union. My grandparents may have known something about Judaism but practiced little. By the time my parents were born, there was even less Jewish awareness.

The only reminder we had of our Jewish identity with the stubborn fifth column in our passports, where the Soviets listed our nationality as “Jewish.”

In the late 1980s and 1990s, the community organized once again and Jewish cultural clubs, aid organizations and even a school were formed. Until this day, in addition to Tallinn, there are smaller Jewish communities in Tartu (a university town), Narva and Kohtla-Järve.

My memories are from this period, when we were once again free to reclaim our heritage; however, not many were inclined to do so in a traditional sense, mostly due to ignorance.

Q: How did you come to rediscover your Jewish heritage?

A: I suppose it began 15 years ago, when my mother began working as a secretary for Rabbi Shmuel Kot, Chief Rabbi of Estonia and a beloved Chabad-Lubavitch emissary here since 2001. The rabbi and his wife have done a wonderful job in reinvigorating Judaism among residents and tourists alike.

My personal connection began in earnest after my older brother and I returned from a trip to Israel under an organization called Mekorot when I was 17 years old. Visiting the Kotel and being in a Jewish atmosphere was very inspiring for me. After that trip, I decided to undergo brit milah (circumcision) and take a Jewish name. I didn’t really understand why, but I knew that I needed to do it.

I attended prayer services for the holidays, but that was it.

The next step came through the STARS program, now known as Eurostars, for college-age Jewish youth to learn about Judaism, organized by Chabad in Russia and franchised in Jewish communities all over Europe. I was recruited by a very persistent rabbi named Inon Assayag who was sent by the World Zionist Organization to assist Rabbi Kot with youth programs.

I began learning more and more. At first, it was all intellectual, but I gradually began to understand that it was not enough just to learn about Judaism. I actually had to live Judaism.

One of the highlights of my Jewish journey from that period was when I learned through the entire Tanach in Russian online within the span of two months. I felt that I needed to get a bird’s-eye view of Judaism, its history and where I fit into it all.

Gradually, I began to incorporate Shabbat and kashrut into my life.

The next milestone was when I moved into my own apartment. I managed to get a place near the synagogue, which allowed me to attend without riding the bus. This is unique here since most Jews live all over the city of Tallinn. My parents had a mezuzah on our home, installed by our relatives who lived there before us, but this was the first time I put up a mezuzah of my own.

Q: What is Jewish life like in Tallinn?

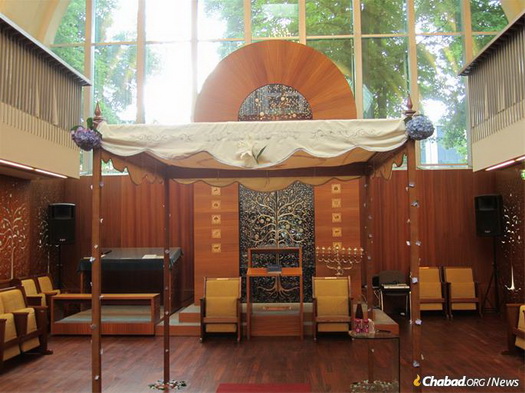

A: There is a large building in the center of the city where the Jewish organizations are headquartered. Right next door is the religious community center, a stunning modern facility with a synagogue, kosher kitchen, mikvah, classrooms and more.

Today, it is very busy, thank G‑d. There are 14 separate regular educational programs for Jewish people of all ages, from toddlers to pensioners and everyone in between. There is a daily morning minyan, pre-holiday programs, classes for women, classes for men, classes for teens and more. This fall we plan on adding classes in Estonian and in English to make sure that every Jew will be able to learn.

We also have an active Smart J chapter—an after-school program for kids to enjoy a kosher dinner, learn about Judaism in an informal setting, and enjoy themselves in a safe and welcoming environment.

Q: You mentioned kosher dinner. Is kosher food available in Tallinn?

A: In addition to the catering facility in the synagogue, a community member recently opened a kosher bistro, where one can get bagels and other kosher fare. (There are also apartments for hire there, and it is within walking distance from the synagogue, so it makes an ideal arrangement for observant tourists or business travelers.) It’s very impressive to see that a community as small as ours can support a kosher restaurant. We are small, but growing steadily.

Q: Is your wife also from Estonia?

A: My wife, Chaya, is from Yekaterinburg, Russia, and had been studying at the Chabad seminary in Moscow when we met. We were introduced through a shidduch. Thank G‑d, we have two beautiful children.

Q: Was she happy to move to Estonia, where the community is so small?

A: This was one of the hardest decisions we had to make as an engaged couple. On one hand, there is a wonderful program in Moscow, where newly married couples are supported for a year by the community. This allows both husband and wife to deepen their understanding of Judaism. It was very tempting for us.

On the other hand, we knew that we were needed here in Estonia. This is my community, and I felt that we could contribute here.

Today, in addition to my work in the university, we create and lead many educational programs for the community, working alongside Rabbi and Mrs. Kot.

We are part of a growing core of committed young local families that serve as an example for others to follow.

Q: Where will your children go to school?

A: You have touched on one of the major issues we are dealing with. There is a Jewish kindergarten, so we are OK for a few years.

There is also a “Jewish school” in the Jewish community complex, but it is actually a public school with Hebrew instruction and rudimentary classes on Judaism. Since it enjoys a good reputation, many people want to send their children there; the majority of the students are not Jewish, and the food is not kosher.

There is a lot of talk right now about the feasibility and sustainability of a Jewish private school. If that will not work, there is the Shluchim Online School, but time will tell.

Q: Has your family also progressed in their Jewish observance?

A: Yes. We never planned it, but it actually happened. My brother was involved before I was, and in many ways, I followed the path that he blazed. He was an active board member of the synagogue for many years and is involved in the discussions about the possible school.

My father was initially not very involved, but Rabbi Kot is such a personable, kind and positive leader that it’s hard not to be inspired by him. Nowadays, my father comes for Shabbat and holidays, and puts on tefillin. The synagogue has become his home as well.

Q: On a different note, there is a lot of discussion these days about anti-Semitism in Europe. What are things like in Estonia?

A: It is likely that there is some anti-Semitism on an individual level, as you have almost everywhere, but it’s not like you hear about in other parts of Europe. In addition, Rabbi Kot and the chairman of the community, Boris Oks, have excellent connections with the political leaders, who have proven themselves to be reliable friends of the Jewish community.

Q: Do you have any final words to share?

A: I just want to reiterate the amazing impact that Jewish education has had and continues to have on people here.

Every day, I see people experience what I experienced. They learn about Judaism and gradually incorporate it into their lives. Middle-aged men and women who lived their formative years under the Soviets are observing more and more, lighting Shabbat candles, putting on tefillin or keeping kosher.

From my STARS group, four of us have started Jewish families. We are told that every individual is an entire world. Here we see “worlds” that are becoming illuminated with Judaism after generations of suppression, intermarriage and neglect.

People are learning Torah, Mishnah, Jewish law and chassidus. Some have made major changes, and others are taking baby steps, but everyone is progressing.

Sparks have been lit, and they are now kindling other sparks.