How This Rabbi Built 30,000 Public Menorahs

by Reuvena Leah Grodnitzky and Carin M. Smilk – chabad.org

It was more than 30 years ago when Rabbi Boruch Klar first heard the Lubavitcher Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, of righteous memory—speak about the importance of lighting menorahs in public places. As soon as the speech was completed, Klar saw groups of young rabbinical students jumping at the opportunity to construct large-scale menorahs for lightings. Their design consisted of PVC piping, painted gold or silver, with electric wiring inside.

“It was amazing how quickly they put these menorahs together,” says Klar, who now directs Lubavitch Center of Essex County in West Orange, N.J., with his wife, Devorah. “They just weren’t so attractive though. I thought, ‘You can’t go to the governor’s mansion with those menorahs. I have to do something about this.’ ”

Klar, who acknowledges that he had no previous background in engineering or construction—or any type of handyman-related tasks, for that matter (he had been a philosophy major in college)—decided to design a menorah out of aluminum. Steel was too expensive and too heavy, and the nature of aluminum’s shiny durability would be beautiful enough to illuminate even the most dignified or exotic locations.

In a time with no Google search engine—with no Internet, in fact—Klar was able to locate an aluminum company in Birmingham, Ala., that agreed to make and cut to measure his design. The structure was shipped by truck back to New Jersey, where an electrician assisted with the wiring, and rabbinical students helped put the first prototype together.

“Our original construction was quite primitive; over time, we have greatly improved upon it,” explains Klar. “But the design has always remained the same: the straight, non-rounded branches, according to Maimonides’ description.

The first year of production, Klar sold 20 menorahs to various Chabad Houses across the country, including one to Rabbi Yossel Kranz, director of Chabad of Virginia in Richmond.

“At one point, we had more than a dozen of his menorahs all around town—in every neighborhood, on various street corners and at all the malls. I don’t think there was a city with more menorahs than we had,” recalls Kranz. “These were the first outdoor menorahs that were pleasing enough, modern enough, friendly enough to use, as well as hardy enough to proudly display in outdoor locations in the community. Most of the others at the time were rather crude.”

Changes in Construction

Klar explains that his goal, from day one, “has always been to make the most beautiful, least expensive, easiest-to-use menorah possible.” Perhaps equally important is the fact that the menorahs can be assembled in about five minutes. “That first round of menorahs was primitive, but it was a lot better than anything else that was out there. It was the only thing I could think of, but it worked.”

The initial design had four legs coming out of the bottom to make the menorah sturdy, with arms bolted into the main stem. Over the years, Klar discovered ways to make it stronger and more appealing to the eye. “The first design was beautiful in its own way; it was the first of its kind,” he states. “There are Chabad rabbis who still have that original design to this day.”

Within three years, Klar was producing 80 menorahs—which meant 80 stems and 640 arms.

The responsibility became too great. It was then that he partnered with an Israeli who owned a New Jersey-based metal factory in order to produce the menorahs; the design became better-welded as a result. Since then, construction has been moved to a factory in China for reasons of cost.

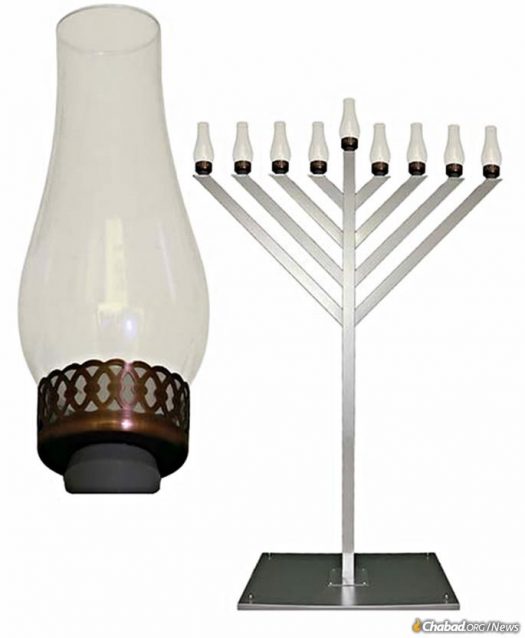

Some of the most noticeable changes to the menorah over time include a square metal base with a projection into which the menorah is dropped (no legs or screws required), bolt-free arms that slide onto the stem, automated menorah-lighting controls and a canvas carrying case. He also recently developed a 6-inch, weather-proof LED bulb for the menorah to be more energy-efficient and to put less pressure on the menorah’s electric components.

Another very practical feature is a lantern-conversion kit that enables users to light the electric menorah with real fire. The bulb is removed and replaced with a brass cup mounted on a heavy plastic base with a thick bulb thread. A liquid paraffin container fits into the brass cup, and a chimney glass covers it; the wick is then lit with a flame.

“The menorah has a clean and beautiful design now,” says Klar. “Now it is as perfect as I can imagine.”

New sizes and types of menorahs are always in the works. To date, Klar’s website offers a 12-foot giant display menorah, a 9-foot large display menorah, a 6-foot indoor/outdoor menorah, a 3-foot electric display menorah and a 22-inch electric tabletop display menorah, in addition to a 2-foot car menorah.

Where Do the Menorahs Go?

Half of Klar’s menorahs are sold to Chabad Houses around the world, and the other half are sold to various companies and organizations, such as U.S. military bases in places as varied as Arkansas, Japan and South Korea; fire departments; theme parks like Disneyland, Universal Studios and Six Flags; sports arenas; corporations; department stores, including Nordstrom; cruise ships; hospitals and nursing homes; condominium associations and apartment complexes; holiday-display designers; municipalities; and government contractors. Klar sells the menorahs to fellow Chabad Houses at a significant discount, while sales from the other contracts support the budget of Lubavitch of Essex County.

Klar reports that he now produces approximately 1,000 menorahs every year, about 30,000 in all. Of course, he’s far from the only maker and distributor of such menorahs these days, but he is amazed at how far it’s come and how loyal buyers tend to be.

“The product is fantastic,” says Kerri Rafferty of Holiday Image, an interior-design and visual-merchandising company. “These menorahs are absolutely gorgeous—a quality product. They exactly fill our need.”

Holiday Image purchases and uses dozens of the menorahs every year in Chanukah displays for large corporations and retail establishments in locations across the country.

In the first decade of menorah production, Rabbi Hirschy Zarchi, who had just opened a campus Chabad center at Harvard University, ordered a menorah just days before Chanukah for a major holiday event that he was to host on campus. Klar was in a bind because he had sold out of them, but wanted to help his fellow rabbi publicize the miracle of Chanukah.

It was just before the event when Rabbi Yossi Lipsker, director of Chabad Lubavitch of the North Shore in Swampscott, Mass., about 40 minutes away from Harvard, called Klar to report that two menorahs, instead of one, had arrived from the shipping warehouse. Klar quickly called Zarchi to inform him that he would have a menorah that Chanukah—the result of a miraculous mistake.

A Personal Connection

Klar, who did not grow up in the Chabad community, says that he never planned to be so involved in menorah distribution.

“Chanukah was always an important holiday for me. It’s a time when many Jews can feel left behind, so that’s why there’s nothing that will attract and affect more Jews than a menorah,” he says. “People come out in big numbers just to see these large-scale beautiful menorahs because it excites them. Regardless of how much they connect to Judaism throughout the year, when Chanukah time comes, instead of feeling alone or forgotten among the various holiday decorations all around, these grand menorahs—standing bright and shining—really make an impact.”

According to Klar, the message of Chanukah is one that resonates with all Jews, no matter where they live or their station in life.

“The symbol of the menorahs represents what Chanukah is all about: that the light of the menorah can never be destroyed; that in the darkness, there will always be that one pure cruse of oil,” he explains. “This is the light of the soul of every Jew. The menorahs light up the spark in every Jew more than anything else.”

And what about him? What keeps him going, tinkering, configuring? From the get-go, he says, “I was determined to make it better. I always wanted to create big—to do something to make a difference in the world. And I’m still determined. I am still excited about it.”