Here’s My Story: The Impossible Kiddush

Mrs. Schulamith Bechhofer

Click Here for a PDF version of this edition of Here’s My Story, or visit the My Encounter Blog.

When we first immigrated to Canada from Holland in 1951, we settled in Toronto. It took some months before we could buy our own home, and our initial accommodations were very primitive – in fact, we lived in an abandoned house which the Jewish community planned to make into a mikveh. But the place was free and it was temporary, so we made due.

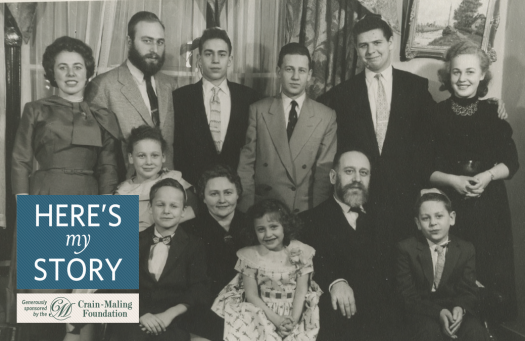

We were a family of ten children. I was already twenty years old, and so I went to work, while my younger siblings went to school. The two youngest ones stayed home with my mother – Obi, who was three, and the baby, Amina, who was not quite two at the time.

It was hard on my mother, because the house had no modern facilities and, to do the laundry, she had to boil water in a big pot on the stove, then haul it upstairs to the bathroom which was on the second floor. One day, when she was going back and forth, she returned upstairs to find Amina submerged in the pot of boiling water!

In a panic, my mother grabbed her and she immediately saw that her skin was coming off her. She wrapped Amina in a sheet, and rushed her to the Hospital for Sick Children. I don’t know how she managed this, because she didn’t speak English, but she ran out into the street screaming, and people helped her.

Later that same day – which was Thursday, November 22, 1951 – I was sent to the hospital to talk to the doctors because I was the only one in the family who was fluent in English, having attended the Bais Yaakov seminary in London. The doctors’ prognosis was grim. “Tell your parents that there is no hope,” they said. “This child is going to die. She is not going to live out the day.”

I didn’t have the heart to tell this to my parents. So, instead, I said, “She is very, very sick, and the doctors are trying their best.”

Indeed, they were trying. They put her in a cast in order to minimize the exposure of the burned skin to the air and retain as much fluid in the tissues as possible. But they really didn’t think that this would help her survive.

Realizing the gravity of her condition, and not knowing who else to turn to, my father called his brother-in-law, Rabbi Chaim Mordechai Aizik Hodakov, who served as the secretary of the Rebbe. Rabbi Hodakov took the matter to the Rebbe, who said that Amina would be alright, and he instructed my father to make a communal kiddush that Shabbat, specifying that my mother be involved in the preparations.

It felt strange to us to be making a celebratory kiddush, but my parents – who were not Chabad chasidim – put on the kiddush because the Rebbe had instructed them to. Word spread in the neighborhood and many Lubavitcher chasidim showed up – they ate, they drank, they danced. They put their all into it, knowing the directive had come from the Rebbe, which meant it was important. And when Shabbat was over, we found out that the Rebbe had been right – Amina was still alive despite the doctor’s worst predictions.

We began to grasp the power of the Rebbe’s blessing, and our trust in G-d was renewed, as our hopes grew.

Luckily, at that point we were still ignorant of the details of her condition. In a child this small, the heat from such severe burns can damage the internal organs, including the heart, lungs and kidneys. The doctors were particularly concerned about her kidneys, and were waiting to make sure that the urinary system was still working. That turned out to be fine, but she was hardly out of danger.

The following Saturday, December 1, was her second birthday, and we planned to go to the hospital on Sunday to celebrate and give her some small presents. Instead, the police came to our door – because we had no phone and the hospital couldn’t call us – to inform us that we needed to rush to the hospital because Amina was dying.

When we arrived, she was in bad shape. It was awful to look at her little face. Her cheeks were sunken, and there were deep black circles under her eyes. I tried to pull my mother away, saying, “Don’t look, don’t look,” but she said, “This is my child. I have to.”

My father called the Rebbe again, and again the Rebbe said that she would be all right. My brother Dovid remembers that, on this occasion, my father spoke directly with the Rebbe who told him, “You are a rabbi. It is your job to see that Jewish education in the city is as it should be, that the kosher standards are good … You must do your job, and G-d will do His.”

While the doctors were constantly trying to prepare us for the worst, the Rebbe continued to sustain our hope, which we clung to as the months passed and Amina remained on the critical list. During this time, there were many setbacks and close calls, as when her fever spiked to 106 and, again, when she began vomiting and deteriorating for an unexplained reason.

In the latter instance, when my father informed the Rebbe, he said, “Ask the hospital to check what they are doing. Something is not right.”

It is very difficult for a foreigner who doesn’t speak the language to challenge doctors and insist that they double-check their treatment. However, the Rebbe’s certitude that the hospital was making some sort of mistake instilled my parents with courage. So they spoke up.

As it turned out, Amina was being given the wrong medicine – an improper injection or something like that. I don’t remember specifically what it was, but I do remember that my parents’ insistence caused the hospital to correct what the mistake.

Amina stayed in the hospital until March, when she was moved to home care. She had very deep wounds, some still open, and her bandages had to be changed constantly. Also, by the time she returned home, she had lost the ability to walk, or even to sit and stand, as a result of having been in a body cast for all those months. She had to re-learn everything. It took months for her to recuperate, but, ultimately, the Rebbe was right – she got better and was able to function normally.

On one particular occasion, the Rebbe sent a golden ruble to Amina with instructions that, when she would get married, she give it to charity on her wedding day. And, indeed, when the time came, she did just that. (I believe she gave the value of the ruble to charity and held onto the actual ruble the Rebbe sent.)

When she became engaged to Yitzchak Newman, he was a bit worried that the trauma her body had suffered as a result of the burns might affect her ability to bear children. He asked the Rebbe about it, but the Rebbe assured him there was nothing to be concerned about.

Indeed, she went on to have sixteen children, which was very unusual in itself. Now her children are raising their own children, so a whole tribe has come out of that miracle.

Mrs. Schulamith Bechhoffer (1931-2018) was the daughter of Rabbi Dov Yehudah and Sarah Shochet. She was a teacher who resided in Queens, New York, where she was interviewed in August, 2012

Bracha

I’ll add she had generally easy births and much less pain than most people…. sometimes hardly any.