The Untold Bar Mitzvah Story of a Brooklyn Dodger

by Dovid Margolin – Chabad.org

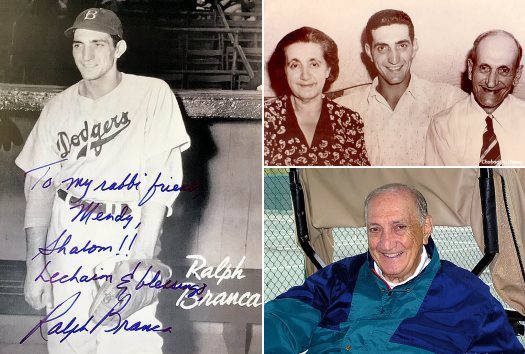

Former Brooklyn Dodger pitching star Ralph Branca passed away early in the morning on Nov. 23 at the age of 90. Most famous for giving up a 1951 pennant-winning home run to Bobby Thomson of the Dodgers’ cross-town rivals the New York Giants—known forever in baseball as the “Shot Heard Round the World”—Branca played 12 seasons in the majors and was known throughout his life as a first-class mensch.

What is perhaps less well known are his Jewish roots. Born to a Jewish mother but raised Catholic, Branca seldom spoke about his Judaism, although apparently was always aware of it.

“Ralph certainly knew about it,” says his nephew, Bill Branca. “The girls in the family, his sisters; they talked about it quite openly. The boys—Ralph, my dad, their brothers—they didn’t talk about it, but they all knew.”

While Ralph may not have had a bar mitzvahat age 13, he did have one years later, at age 84, when he first met and eventually wrapped tefillin with two Chabad-Lubavitchyeshivah students at his office in Rye Brook, N.Y.

Never Heard of Him

It was the winter of 2010 when Yisroel New and Mendy Marlow were making their weekly Friday afternoon trek from their Chabad yeshivah in the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn, N.Y., out to Rye Brook in Westchester County. Like thousands of similar Chabad rabbinical students their age around the world, the 19-year-old boys spent their Friday afternoons taking part in the mitzvah campaign of the Lubavitcher Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—visiting Jewish businesspeople at the end of the work week to share a Torah thought for the week, offer Jewish men the chance to wrap tefillin and distribute Shabbat candles to Jewish women.

Arriving at a massive office complex called 800 Westchester Avenue, the yeshivah boys set up shop in the business center’s food court, hoping to meet Jewish business men and women on their lunch break. Two Chassidic yeshivah students in black hats and dark jackets isn’t the most common sight in a suburban office food court, and they met a fair number of curious people—Jews and non-Jews alike—with whom they engaged and often formed connections.

And that’s where they met Ralph Branca.

“Every week, we saw this really tall guy sitting at a table during his lunch break reading the paper,” recalls New. They finally approached him.

“You must be the Yiddish boys from Brooklyn,” the tall man told them. They talked; the man was warm and friendly.

Then he introduced himself: “I’m Ralph Branca.”

At the time, the yeshivah boys, to Branca’s surprise, had never heard of him.

“When you get home, you can look me up,” the three-time All-Star told them. “What are you guys doing here, anyway?”

They explained what they were doing, and Branca, who worked at an insurance firm in the complex at the time, invited them to come by his office the next week, telling them he’d round up some of his Jewish colleagues.

‘L’Chaim’ and Other Yiddish Words

The next week, Branca played some offense for the students, calling in his Jewish co-workers and introducing them to the boys from Brooklyn. The visits continued weekly, with Branca always gracious and welcoming, recall New and Marlow, regaling them with tales of his baseball career: He told them about his 3.79 career ERA, how the Giants stole the signs leading up to Thomson’s homer and his career-ending injury.

New chalked up Branca’s relatively familiar Yiddish-word dropping to the pitcher’s New York roots, having grown up, as he told them, around Jews and Italians. (Incidentally, the Dodgers’ old home at Ebbets Field in Crown Heights was only blocks away from Lubavitch World Headquarters at 770 Eastern Parkway.)

“He was writing his book, and he had this machine that he would dictate into,” relates New. “He was very excited about it. He’d be saying ‘l’chaim’ into it to show you how it worked.”

Branca enjoyed trying out some saltier Yiddish words on his Dragon dictation machine as well.

When he told the boys that he was the third youngest in a family of 17 kids, New balked. Seventeen children in a family sounded more like a Chassidic Jewish family to him—and that’s what he told him.

“Funny that you say that,” New and Marlow remember Branca replying. “My mom was born Jewish.”

‘He Wanted to Know Everything’

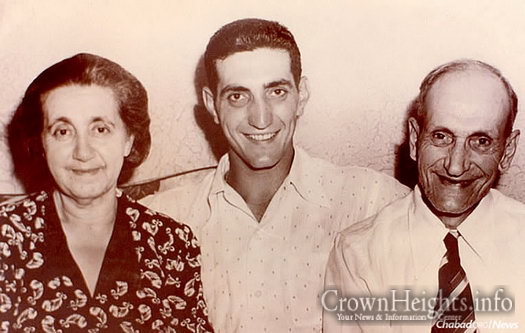

Branca’s mother, Katherine (Kati) Berger, had been born to a Jewish family in Hungary, immigrating to America in 1901 at the age of 16 (some of her siblings later perished in the Holocaust). His father, John, was an Italian Catholic, and Branca and his siblings were raised in the Catholic tradition. Of course, according to Jewish law, being born to a Jewish mother made Branca as Jewish as Moses, and that’s what the yeshivah boys told him.

“We hadn’t realized that he was Jewish,” says Marlow, “but everything he knew started making more sense to us.”

Branca told the boys he had never practiced Judaism and therefore did not feel himself to be a Jew. The boys responded that he was still Jewish and offered him to wrap tefillin with him for the first time.

“We told him about the idea of a mitzvah, and how each and every individual mitzvah counts,” says New. “When somebody gives tzedakah [charity], that $20 might not mean much to him, but it means a lot to that needy person who receives it. A mitzvah is the same. It might not mean much to him, but it matters very much to G‑d.”

“This week, I’ll do the tzedakah one,” Branca replied with a smile. As he had done every week, he folded up a $20 bill and slipped it into the boys’ pushka charity box.

New and Marlow were back the next week, again offering to help the right-hander put on tefillin. This time, Branca agreed.

“We wrapped the tefillin with him, and then said the Shema prayer in Hebrew and English,” says New. “In the beginning, it was like he was doing us a favor, but that changed as it went along. He wanted to know everything: Why do we wrap it seven times? Why on his left arm? We pointed out that the way we wrap the tefillin spells out one of G‑d’s names in Hebrew. He was fascinated.”

Branca’s right arm had made him famous, but his left arm had allowed him to pray as a Jew, connecting to the Jewish soul deep inside.

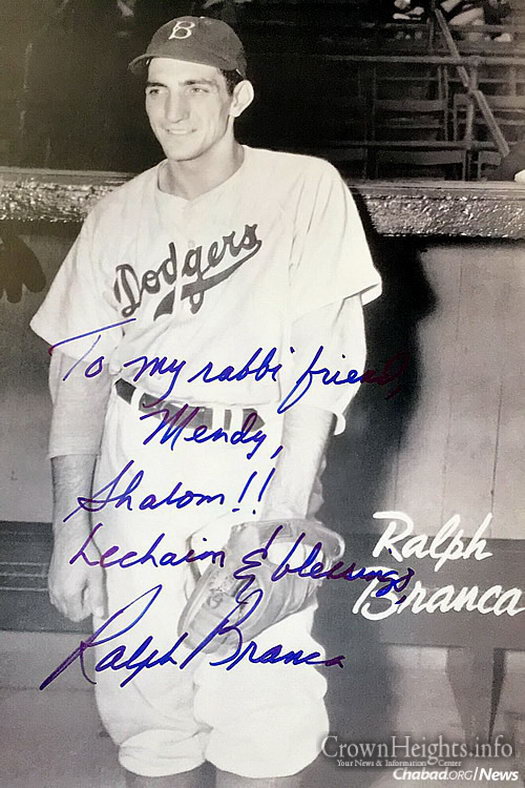

That day, Branca pulled out two photos of himself from his baseball heyday and signed them for his young rabbi friends: “To my rabbi friend, Mendy,” he wrote on Marlow’s picture. “Shalom!! Lechaim & blessings, Ralph Branca.”

A fan

Thanks for posting this story. I never heard of Mr. Branca but he made a home run with putting on tefillin and encouraging others to also.

Excellent story.

This is a great story. Never heard of him but it’s so nice how he accepted the fact that he was Jewish and did mitzvos willingly.

Let’s Go Yankees.