Leibel Mochkin, 95, Daring Chassidic Activist in the USSR and Beyond

by Menachem Posner – chabad.org

Everyone in the Soviet Union knew what to do if you were arrested by the Secret Police: You shut your mouth, averted your gaze and tried to be inconspicuous. Everyone, that is, besides Leibel Mochkin, who died last week at the age of 95.

Young and strapping Leibel learned early in life that some rules were meant to be broken, especially when lives were at stake. He would recall how after one arrest, he struck up a conversation with the agent who arrested him; soon, that agent was part of the network of officials and bureaucrats who were paid off to look the other way as thousands of Chassidic Jews were smuggled out of the Soviet Union on forged passports.

Born in early 1924, Yehuda Leib (known as Leibke or Leibel) Mochkin was the fourth child of the legendary Chabad Chassid Reb Peretz and Henya Mochkin, who were then serving as emissaries of the Sixth Rebbe—Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, of righteous memory—in the Ukrainian town of Semyonovka (Chernigov Gubernia, then part of the Soviet Union).

During those years, when Jewish education could be punishable by death, the Chabad yeshivahs had all gone underground, and Leibel received his education informally, studying snatches of Hebrew, Chumash (The Five Books of Moses) and Mishnah whenever he could. Shortly after his bar mitzvah, his parents sent him to Berditchev to learn in the underground yeshivah there. After a few months, when things became dangerous, he relocated to another yeshivah.

During the course of his wandering from yeshivah to yeshivah, he was deeply influenced by Chassidic mentor Reb Mendel Futerfas. In him, Leibel saw an utterly devoted Chassid and activist who was never afraid to challenge the system, an ideal he would identify with and make his own.

Already as a teen, he became active in the vast network of underground Jewish institutions established by Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak—illegal under the enforced atheism of Soviet rule—which spanned the Soviet Union. A significant part of his work entailed providing for the physical needs of the yeshivah students in far-flung locations, necessitating travel across the length and breadth of the Soviet Union.

Sporting a leather jacket and stylish pouch, he looked the part of a dashing, debonair young man on a mission. Devoted to fulfilling Judaism in the best manner possible, he procured a tiny pair of tefillin, which he would hide in his jacket wherever he went.

While living in Moscow one year, he and his friends daringly built a sukkah on the balcony of a local synagogue. To keep it from being discovered, they built it only as tall as the balcony railing, so that one needed to lie down in order to celebrate the holiday under its web of boughs.

With the outbreak of World War II, Leibel joined the thousands of Chassidim fleeing from the Nazis in Central Asia. There, far from Moscow and Leningrad, they enjoyed a brief respite from the hounding of the Soviet authorities, whose attention was diverted by the war efforts.

Smuggling to Safety

Upon the conclusion of the war, the Soviet regime redoubled its efforts on eliminating the practice of Judaism. Those involved in the “counter-revolutionary activities” of practicing and supporting Jewish life were once again targeted. After some fortuitous investigating, Leibel discovered that the Iron Curtain was temporarily lifted for Polish refugees who had survived the war in the USSR. Thus was planted the seed that led to the clandestine operation of smuggling more than 1,000 Jews who had never lived in Poland out of the USSR with doctored Polish passports.

Stationed in Lviv (also known as Lvov or Lemberg), Leibel was the leader of a group of heroic Chassidim who orchestrated the flights on the echalonen, as the refugee trains were known.

His duties were many, including arranging safe houses where the Chassidim could be hidden until the departures of their trains, procuring and “editing” the passports as necessary, and maintaining a network of well-paid “friends” in high places.

Every step of the way was highly illegal and entailed significant danger. Leibel was arrested several times during those critical months in 1946 and 1947, including the time when he met one key Soviet agent he was able to bribe, who he called Kiva. As long was Kiva was “working” for him, he would recall with pride, not a single Chassid was arrested.

In what turned out to be the last echalon to leave, Leibel was aboard the train as it was preparing to depart. Having paid off the conductors, he was busily working on the paperwork, ensuring that all of “his” people would be able to safely traverse the border on their way to freedom.

Unbeknown to him, the train began pulling out of the station, and he soon found himself bound for the West. Many of his fellow conspirators, including Reb Mendel Futerfas, Mumme Sarah Katsenelbogen, and his own brothers Mulleh and Yosef were not so lucky. They spent years in the infamous gulags as a “reward” for their heroics.

In fact, Reb Mendel would find the miniature tefillin Leibel had unwittingly left behind and kept them with him for the duration of his stay in the Soviet Union, including the years spent in the gulag.

In France, Leibel married Chaya Rivka (Riva) Shimanovitch, and they began a family. Yet Leibel was not one to settle down. He was always up for a challenge, looking for a wrong to right.

Arriving in the United States in 1956, the Mochkins settled in the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn, near the Lubavitcher Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory. Ever the irrepressible activist, Leibel heeded the Rebbe’s call and threw himself into a slew of communal endeavors, ranging from founding schools to procuring buildings for community organizations.

A longtime project of his was sending agents into the USSR under the auspices of Ezras Achim, an organization he founded along with fellow Chassidic immigrants from the Soviet Union. The emissaries would bring Jewish articles, literature and supplies. While there, they would teach Torah and encourage the Jews still trapped behind the Iron Curtain.

In the early 1970s, as “white flight” beset Crown Heights, the Rebbe called for acquiring buildings for fcommunal use. Leibel sprang into action and personally negotiated the acquisition of the iconic “Farband” building, for which he provided a deposit. Today, it serves as the headquarters for Lubavitch Youth Organization and the Kollel Menachem, an institution of higher learning.

Upon the closing of the Tog Morgen Journal, the Rebbe shared his wish that a Yiddish newspaper with a traditional Jewish viewpoint be founded. Led by Gershon Jacobson, Leibel and Mendel Shemtov founded and financed the Algemeiner Journal.

When the Rebbe issued a call to expand the synagogue at 770, Leibel was soon seen on a Friday afternoon with a steel bar in hand, single-handedly breaking down a brick wall. Strong in muscle and mindset, he was literally unstoppable.

In 1979, When the Iranian Jewish children were being brought to Brooklyn, Leibel was active in assisting Rabbi JJ Hecht in providing every aspect of their care, including cooking meals. And when he saw that visitors from out of the country needed a place to stay, he arranged lodgings for thousands of French Jews who had come to spend the High Holidays and Sukkot in the Rebbe’s presence.

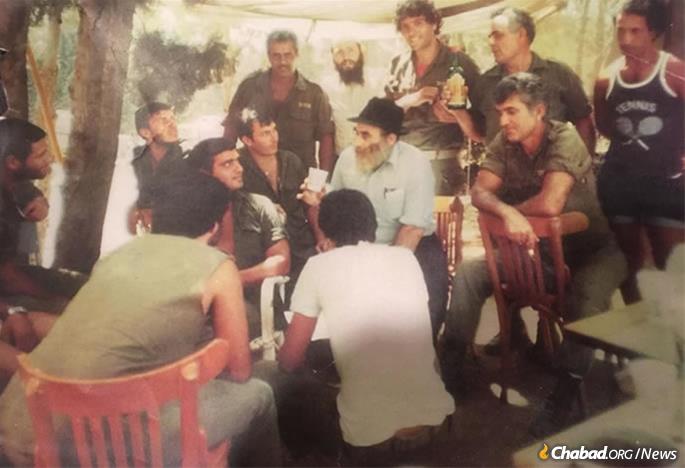

When the Lebanon war broke out in 1982, he went to the front to support the soldiers. The family still has video footage showing him putting on tefillin with soldiers at the Beirut airport. The sound of exploding bombs is clearly heard throughout, and raging fires can be seen in the background.

Yet his passion remained Torah study. Following a commitment he made to the Rebbe on Purim in 1966, he was particular to learn the entire weekly portion of Likkutei Torah and Torah Ohr. This continued until the final week of his life.

In his late 70s, Leibel had more time to devote to learning and would often be found in the central Chabad yeshivah at 770, learning among the students, feeding off and inspiring their youthful energy. As was his way, Leibel arranged for new tables for yeshivah students and raised money to renovate an aging dormitory, procure new beds for the boys and improve meal plans.

In 2005, when it became clear that Israel’s Prime Minister Ariel Sharon intended to unilaterally pull out of the Gaza Strip, he was determined to travel there himself to show solidarity to the residents of Gush Katif. Despite news reports that no one was being allowed to enter, Leibel, at the advanced age of 80 years old, snuck into Gush Katif and remained there until he was carried out during the forced evacuation.

Active in the import-export business, he would often donate generously and solicit others to do the same. His list of pet causes constantly evolved and expanded throughout his life, including providing funds for families in need.

Leibel Mochkin is survived by his wife, and their children: Rochel Kaplan (Montreal), Yosef (Brooklyn, N.Y.), Lena Cohen (Passaic, N.J.), Faigy Fellig (Miami Beach, Fla.), Levi (Melbourne, Australia), Shimon (Brooklyn, N.Y.) and Mendel (Brooklyn, N.Y.); and by siblings Rabbi Berel Mockin (Montreal) and Gutta Schapiro (Brooklyn, N.Y.). He was predeceased by his elder brothers, Shmuel (Mulleh) and Yosef Mochkin.